Interview: Wayne Levin

Through a Liquid Mirror: The Life and Work of Photographer Wayne Levin - From Activism to Underwater Artistry

Hawaii based photographer Wayne Levin reflects on his lifelong career while preparing for a retrospective collection of his journey from underwater photography to documenting the civil rights movement. Wayne shares experiences from his collaborations, notably with Tom Farber, highlighting significant projects such as documenting Hansen's disease communities in Kalaupapa Molokai and the spiritual importance and military impacts on the island of Kaho'olawe. Wayne reflects on his involvement in the civil rights movement and serving in the Navy in this interview.

Wayne explores themes like the boundary of air, water, and land in his projects and continues to delve into humanity's place within larger ecosystems. This expansive interview encapsulates Wayne's artistic evolution, his philosophical reflections on individualism, collaboration and his deep connection to Hawaii's natural landscapes.

There is something really magical about Wayne’s photographs, he captures an essence and spirituality of space/place. I hope you enjoy this conversation with this inspirational photographer.

“The artist’s intention is not exactly to reveal the world beneath the surface, but, rather, to deepen the mystery”

-Thomas Farber, from introduction of Through a Liquid Mirror

Kudos to Thomas Farber for connecting me to Wayne.

All Photography Copyright Wayne Levin

Music Sample from Martha Argerich Ravel Gaspard de la nuit I. Ondine

Time Stamps

00:00 Introduction to Wayne's Artistic Journey

00:28 Collaborating with Tom Farber

02:44 Early Fascination with Photography

04:51 Involvement in the Civil Rights Movement

09:34 Experiences in the Navy

21:08 Transition to Underwater Photography

31:43 Navigating Legalities and Permissions

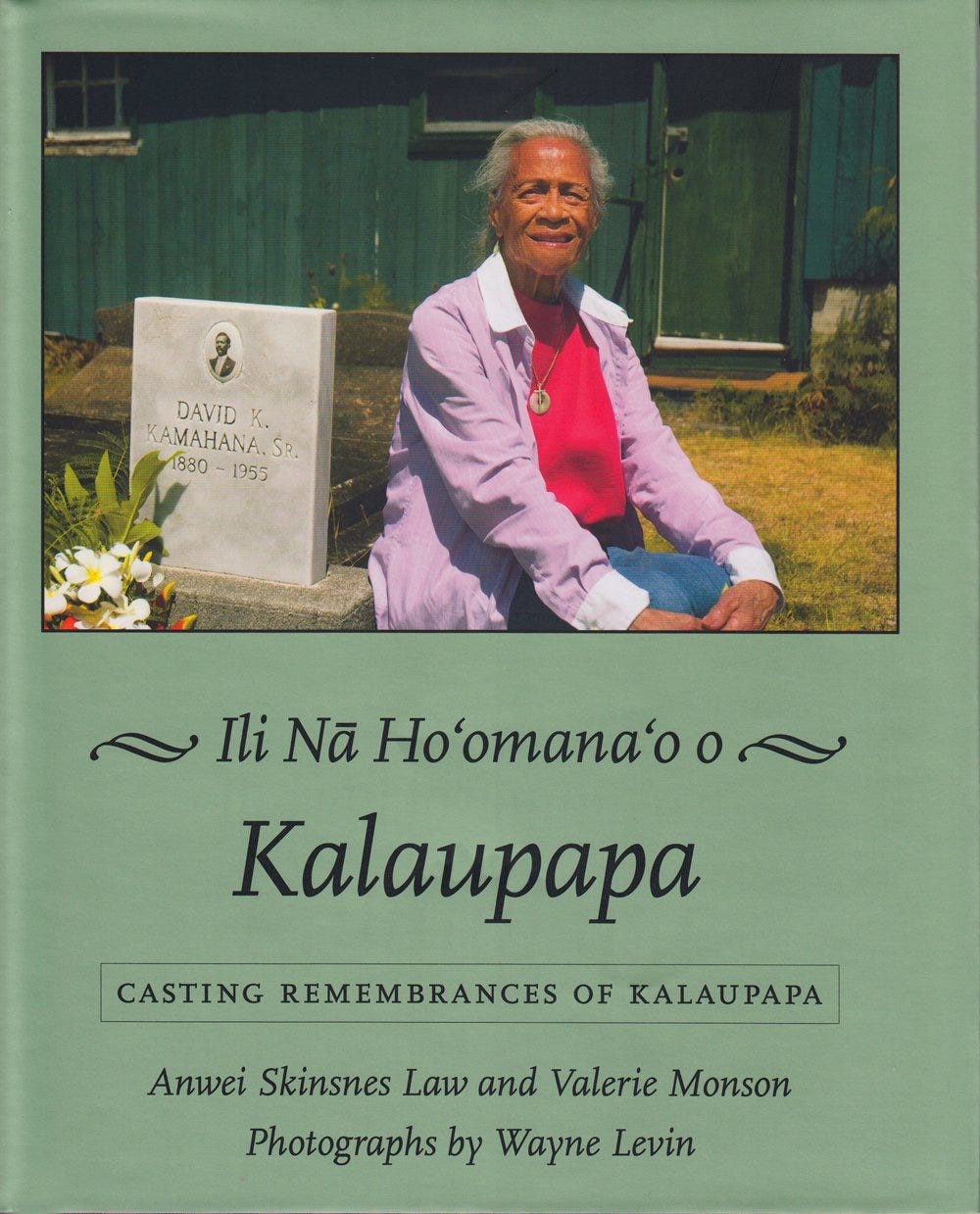

32:41 Reflecting on the Kalaupapa Project

33:40 Documenting Hospice of Dayton

35:39 Exploring Kaho`olawe

40:10 Teaching Photography and Artistic Communication

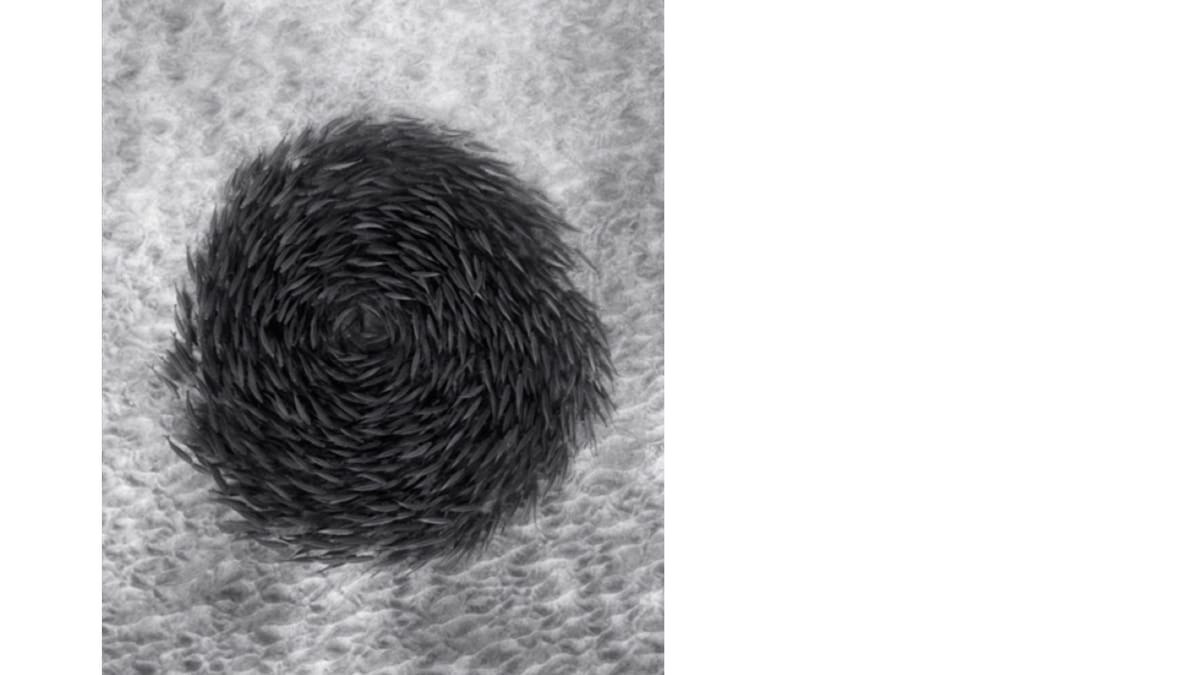

41:30 The Akule Fish Schools Project

44:52 Spirituality and the Concept of the Individual

46:00 Relationship with Hawaii

46:58 Mountains and Clouds: A New Perspective

49:41 Current Projects and Future Endeavors

53:07 The Role of Collaboration

54:55 Political Engagement and the US-Mexico Border

59:48 Thoughts on Aging and Preparing for a Retrospective Show

01:01:45 Daily Routine and Ocean Photography

01:04:44 Music and Artistic Inspiration

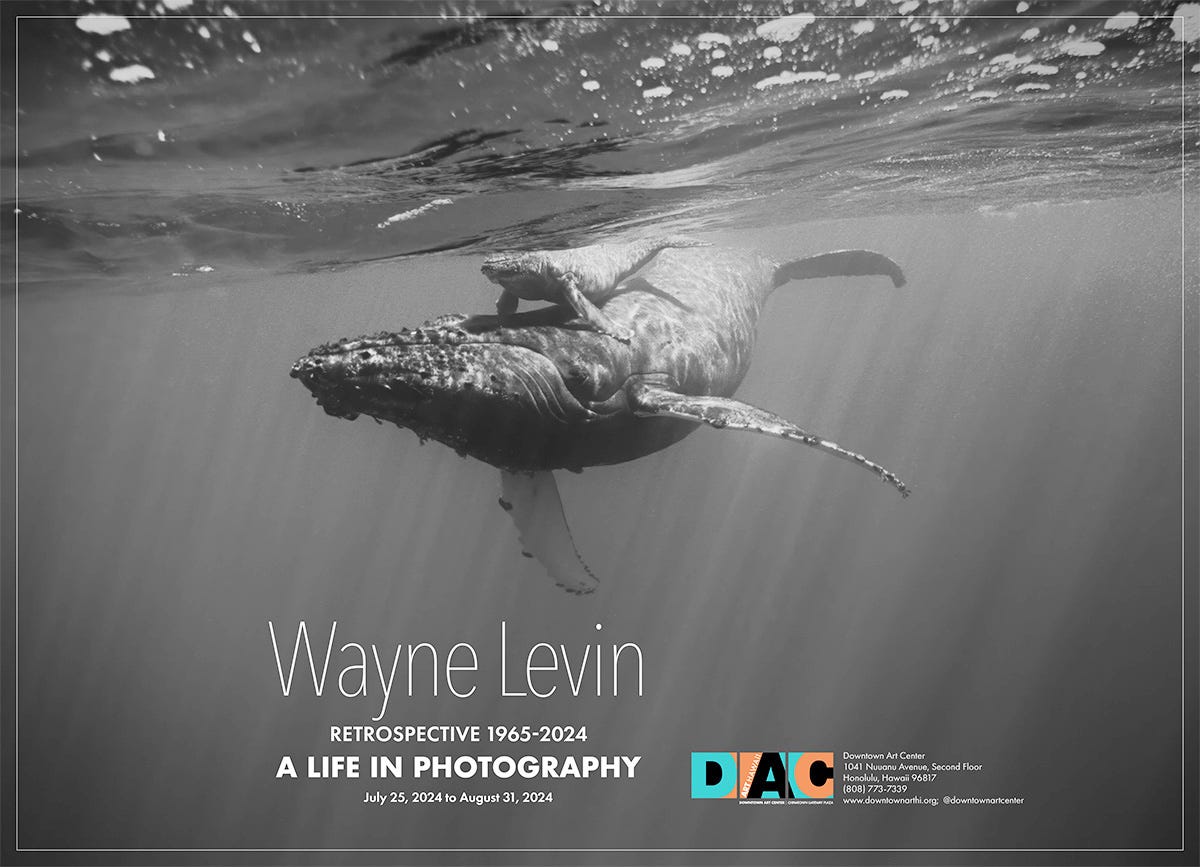

Retrospective July 25th, 2024 to July 31st 2024 @ DAC Honolulu

Transcript

Wayne Levin:

What I want to do is communicate something, the feeling and an idea within me to somebody else. And as an artist, my, job is putting it out there, how they interpret it is their Kuleana, it's their idea.

Leafbox:

Wayne, thank you so much for your time and for being so punctual. I love your photography. I think the first question I wanted to ask is, how it's been working with Tom Farber across the years. Maybe we can start with that, or if you want to start, what first draw you to photography when you were 12? Either one.

Wayne Levin:

Okay. Yeah. It's been great. It's been a great relationship. It started when Tom called me up and wanted to come to the house and he was pretending to want to buy a print, but he really just wanted to meet me.

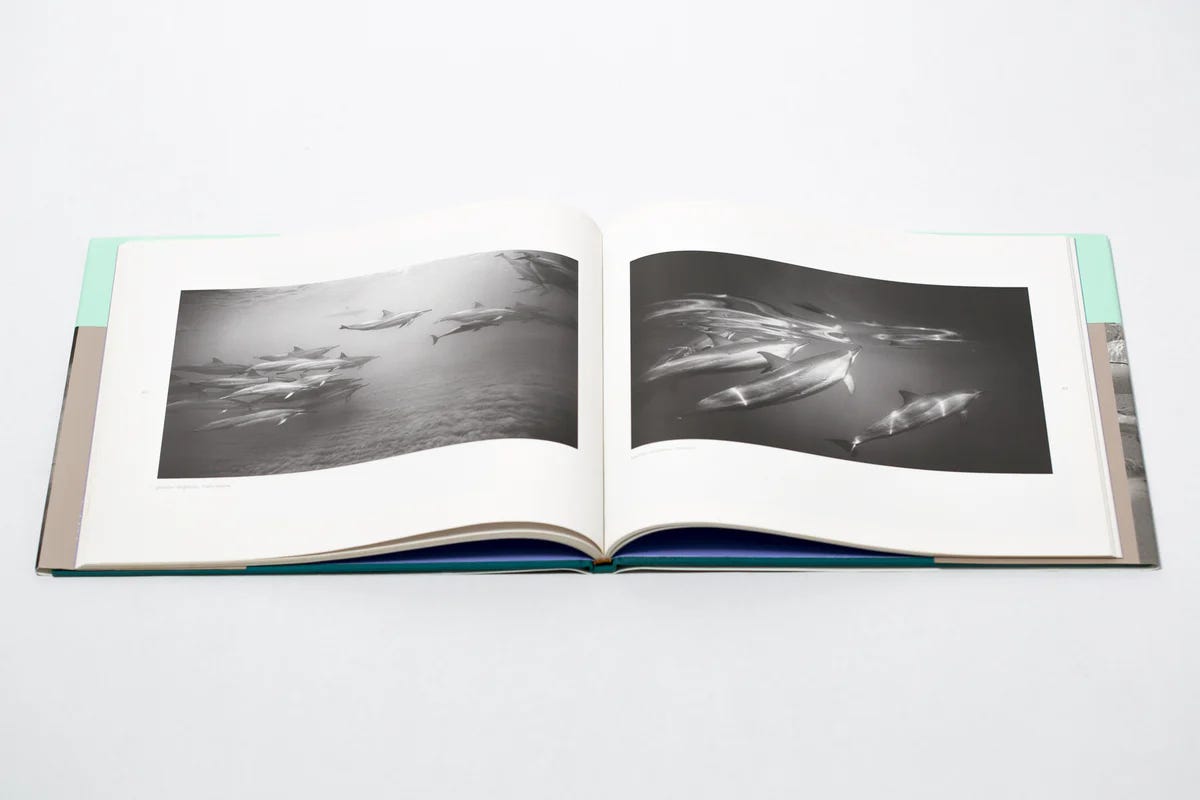

So I showed him prints and that. And then later he came to Kona and we dove [00:01:00] together here and and actually later, we got an assignment together to go to Cocos Island off the Pacific coast to Costa Rica together and dive. And when I wanted to produce my first underwater book it was Tom who really led the way, he was just much more adept at dealing with publishers and spoke to a local Hawaii publisher Gaylord Wilcox.

And lo and behold, after a meeting they decided to publish my first underwater book, which was Through a Liquid Mirror. And then we worked together on another book another one of my books, which was called Other Oceans, which was about aquariums throughout the world. Actually University of Hawaii Press published it.

And I had previously photographed a lot of the aquariums on the east [00:02:00] coast of the U. S. Including the National Aquarium in Baltimore. But when I went to press, they said they only do Pacific Rim they only were interested in publishing Pacific Rim So I couldn't use any of my East Coast pictures, so instead I decided to go to Japan, which had a lot of incredible aquariums.

So anyway, Tom and I worked together on that book, and I've worked with him on some of his books. And we've continued our friendship. It's been a long time since he's got to Kona, but when I'm in Honolulu and he's there at the same time, we always get together.

Leafbox:

So Wayne, why don't we walk back to, I think you first started photography when you were just becoming a teenager.

What was, what drew you to photography and where were you and where did you grow up?

Wayne Levin:

Oh, what drew me to photography was I my, when, I [00:03:00] think it may have been my 12th birthday or something, my dad bought me a Brownie camera and a little develop yourself kit that we set up in the bathroom, and, I took pictures and I was able to actually, see the magic of the print coming up.

And I was hooked, and I, went everywhere with my little brownie. I liked looking through the car window through the through the camera. I remember we took a trip to Mexico, and I remember photographing there and other places. So when I graduated high school, instead of I'm going to a regular college.

I went to Brooks Institute of Photography and studied photography. I ended up dropping out of Brooks to become active in the civil rights movement. And that's a whole nother story, but yeah.

Leafbox:

So just for people to know, where did you grow up in the U. S. or where?

Wayne Levin:

Oh, in Los Angeles.

Leafbox:

And [00:04:00] what was the the culture of, just that was the booming California What was the period of growing up there like?

Wayne Levin:

Oh, what was it like? I, we lived in a, a late 40s middle class housing development, and there were a lot of kids there. So I had a good time with my friends. High school was a little more challenging for me. But, but my really close friend friendships were my neighbors, the kids I grew up with and then later my dad was a doctor, so we moved to one of the canyons up above L A and It was a really nice neighborhood, but I never really connected with the kids there. I guess by that time I was a teenager. I stayed connected with my old friends in the old neighborhood. Yes.

Leafbox:

So Wayne, what, after the Brooks Institute, you drop out and then what's this about the civil rights movement?

You're taking photos or what? Tell us about [00:05:00] that.

Wayne Levin:

Oh, okay, so I was going to a photography school in Santa Barbara called Brooks Institute and I was living in a boarding house with some students at UCSB University of California at Santa Barbara, and a few of them decided to organize a protest when Barry Goldwater came into town, it was during his campaign, and I went along to the protest and I thought that was pretty cool.

It was interesting. And then my family lived in L. A. and I was going to school in Santa Barbara and a lot of weekends I'd drive back to L. A. and spend time there and then I heard about demonstrations going on, civil rights demonstrations at the L. A. City Hall. So I went down and joined them. and became really involved.

I joined CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality during that time and dropped out of school, dropped out of Brooks [00:06:00] Institute, became really involved in the civil rights movement, and then when the Selma Montgomery March came around we, the LA CORE sent a group of Members to the last day of the March to Montgomery, so I decided to go along.

I borrowed my dad's 35 millimeter camera when I went over I went there for the last day and I took pictures and I had lost the pictures. I thought my feeling about them was that they probably weren't very good. But then just several years ago maybe three years ago or so, I was going through some old slides and I found these pictures that I took that at the March on Montgomery and looking at them, technically, they weren't that great and they had mildew.

But I thought they were really interesting. There are pictures I took from the [00:07:00] midst of the March. So I I immediately scanned them. And actually had a little show in Honolulu of that work and I put them on Instagram and then a a company that was producing zines saw them and wanted to do a zine of that work.

So anyway, I published it. I think I found 27 pictures, so I published them in a little zine and I had a show of them, and now I'm having a big retrospective show in Honolulu my life's work, and the earliest work in that show is the work from 1965, that March on Montgomery.

Leafbox:

And when was the zine published?

Wayne Levin:

Oh I would think it was let's see, maybe about 2021 or 2022. I'm not, I'd have to look at it to be sure.

Leafbox:

So this is during, is this post kind of the George Floyd? Black Lives [00:08:00] Matter protests, or is that before that? Oh, say that again. I'm sorry. Was this discovery of this Alabama photography, was that post George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter?

Wayne Levin:

This was 1965.

Leafbox:

No, the zine, so reconnecting.

Wayne Levin:

Oh, the zine. I think it may have been a little bit post George Floyd.

Leafbox:

Was there any response to the correlation or kind of the protests at that time during COVID? How did you respond to those?

Wayne Levin:

More when I had this show in Honolulu.

I got comments that, it's really timely now. So yeah, it must have been post Black Lives Matter.

Leafbox:

Did you have any thoughts about the serendipity of that, or did you have any thoughts about the protests in 2021, or did you want to shoot them?

Wayne Levin:

I wasn't really thinking about that so much.

I was I was thinking a lot about, to the degree things have changed and to the [00:09:00] degree things haven't changed since then. And also that the way that those photographs really showed, a moment in time, it's all of a sudden I was living history myself, and I have these photographs of a time that's really past, an important time.

But I wasn't really in my mind, I wasn't relating it specifically to the George Floyd incident. Incident or to black lives matter, but I think other people who saw the work were.

At the Alabama Capitol with Huge Old Time TV Cameras

Leafbox:

So after that you I believe you joined the Navy. What motivated you to join the Navy? And what was that experience like?

Wayne Levin:

I became really active in the civil rights movement and lost my student deferment because I dropped out of school and I went with a couple friends one black guy and one white guy from the L.A.CORE to, we wanted to work on voter [00:10:00] registration in the South, so we wanted to work with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, SNCC, to work on voter registration we had a couple friends.

I think we came very close to being killed in Mississippi. We, it's an interesting story. We I remember driving through Arkansas and being trailed by a policeman and in a mountain road. And when we, I went around the turn, I would accelerate to get. A little bit away from him and then he slowly creep up.

But anyway, we ended up crossing the border and going into that this town Clarksdale, Mississippi, which was a town where the black guy who was with us had relatives. So we get into Clarksdale. And were pulled over immediately by a cop, and he was like a stereotypic southern policeman, in a way, really big fat guy.

[00:11:00] And we had the mistake of having civil rights and leftist literature in the back of the car, and he saw that and became really upset, and was Took out his gun. He was waving it around at us and saying, you guys either get your ass out of town immediately, or I'm going to throw you guys in jail.

So I said that we'll get out of town. I was about to drive out of town, and Andre, the black guy with us, said, no, they'll be waiting for us as soon as we get to the outskirts of town. And he, so we went to his relative's house, and they let us in and put us up overnight. And the next morning We drew, drove straight to Atlanta without stopping.

And I think he was right. In retrospect, I think that if we had tried to leave that night, they'd have been waiting for us [00:12:00] and, we could have died just that other group Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner [Note: Name Correct Post Audio] had died. But that's what I think. Anyway, I, I started working for SNCC in Atlanta.

And then I got my camera stolen, and I was upset about that, so I drove up to Washington, D. C. and worked for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party for a I was working for an attorney who was working for them, and then my dad called me and said, You're about, you lost your student deferment and you're about to be drafted.

So I pretty much drove straight from Washington D. C. back to L. A., ended up joining the Navy Reserve before I could get drafted in the Army, but after a year in the Reserves, I was called up and spent a couple years on a carrier. Some of it was South Vietnam. So

Leafbox:

Wayne, what [00:13:00] was your strategy? Why did you join the Navy Reserve?

Was that an attempt to, I thought it was safer. Got it. And then what was your consciousness like being,

Wayne Levin:

Oh, at that time I was against the war, I had signed a petition against the Vietnam war. So I was, actually, to join the Navy, I was going against my conscience, but at that time, my alternative would have been leaving the US.

I don't know, maybe I could have gotten back into school and got my deferment back. But I was, because of my camera being stolen, I was actually a little disheartened with the movement at that time. They got me at a soft moment, and yes, I joined the Navy.

Leafbox:

What was the experience like the Navy did you just

Wayne Levin:

Oh, it was pretty I ended up on an aircraft carrier But my job was actually very boring.

I was an aviation storekeeper So I had a store most of the [00:14:00] time I had a storeroom, three decks down below the surface with airplane parts and I basically sit there and read all day and maybe Two or three times a day, somebody would come with a chit to get a airplane part, so I'd look for it and get the part, find the part for him, and he'd sign it, and I'd give him the part.

The only time we really did a lot of work was when we got into harbor and then we'd be loading airplane parts, sometimes big parts like engines, into the holds but,

Leafbox:

And at that time, you didn't have a camera, right? So you couldn't shoot any of this experience, did you document any of your experience in the Navy or shoot anything there?

Wayne Levin:

I had a camera but I don't remember photographing in the, actually in the Navy. Actually, I wanted to, I was in the storekeeping unit and I wanted to get into the photography unit. I already had a lot of schooling in photography and the, Chief, the head of the photography [00:15:00] unit wanted me to go to, to go into the photography unit, but my aviation storekeeper, when I asked him, he put me on mess duty, which was horrible, had to get up at, four o'clock in the morning or whatever.

And I hated it. So after two weeks of mess duty, he called me back to his office and said I'm going to take you off mess duty and I said, Oh, thank you. Thank you. And he said, but forget about photography. And I said, okay, whatever, just get me off mess duty. So that way. But on the other hand we went to some pretty interesting places.

When I was in the Navy, went to Japan a bunch of times, went to the Philippines, Thailand, Hong Kong, and I got, and I bought my first Nikon camera. SLR with like 191 (dollars), I happen to remember that figure, for a camera really top of the line Nikon camera. So [00:16:00] I bought that and I, when I got to these places, I was into traveling there.

And so I did. Photograph that I do remember my photography of my travels when I was in the Navy. And then also that got me really hooked on the travel bug. So after getting out of the Navy, I took a trip. through the South Pacific, ended up traveling around the world for a year and a half.

And then after that trip, I went to Japan and Korea for six months traveling. And that work was my first my first one man photography show in Hawaii. And then after that trip, I took a through Mexico and Central America for four months. Which culminated at my second photography show.

Leafbox:

So where even before when you were in LA you had that travel bug going to the civil rights.

Where did that, did [00:17:00] you always have that kind of drive to explore or where did that come from?

Wayne Levin:

A little bit. My only trips out of the U. S. before joining the Navy was a few trips into Mexico. Not too far.

Anyway, it wasn't too far in. But I did, I really loved trains. And me and my grandmother would take train trips to see my relatives in Portland when I was a kid, I loved the trains I still do and so that was, and then we took trips as a family, going to some of the national parks and So I really did enjoy traveling.

I didn't, I wouldn't consider myself like a hardcore traveler at that time, but after getting out of the Navy, I became hardcore traveler.

Leafbox:

And then the last question I have about the Navy, what was the general [00:18:00] vibe like among the soldiers? Were you all against the war? Were there people, were you actually seeing, what was the general vibe of the soldiers on the boat?

Oh, and the Navy.

Wayne Levin:

I would, having gotten out of the civil rights movement, which I didn't tell them about it was pretty racist, it was shockingly racist. I think that there was a lot of using the N word, a lot of just very racist talk. And I just I don't remember really confronting people on that, but I do remember somehow getting into a few arguments about that.

Leafbox:

But were most of the soldiers, loyal to the regime, or were they critical of the Vietnam War, or were they just drafted and angry? Oh, they were my,

Wayne Levin:

They were mostly there wasn't much talk against the war, but there was a lot of talk against the military, the Navy in a, against the, how rigid the lifestyle was.

And a lot of people couldn't wait to get out.

Leafbox:

And then when you guys [00:19:00] ported in cities, what was the culture of, I always have the image of the prostitution and the navy. Sailors going pretty wild in each port. What was the experience like that? Did you stop in? You stop in Okinawa, or were you guys debriefing? And then there's just a, what was the culture when you were off the boat?

Wayne Levin:

Oh, when we were off the boat, going to bars, yeah, going to, yeah, prostitution. There was a lot of that.

But yeah, a lot of going to the bars, getting drunk.

Leafbox:

What about drug use? Was there psychedelics at all starting to influence the Navy or your kind of environment? Were drugs being part of the scene? I'm just curious if any of that culture had an effect on you, like the 60s.

Wayne Levin:

I heard that at the same time on shore in Vietnam, drugs was pretty pronounced, but on the ship, no it was pretty much all drinking. It's pretty much all alcohol. Yeah. I don't remember any [00:20:00] incidents with drugs, with. Marijuana or anything.

Leafbox:

So what brings you to Honolulu? Is that when you're first porting there or what?

Wayne Levin:

Oh, no. My family moved to Honolulu when I was in the Navy. So in 1967, they moved. And when I was discharged in 68, I followed them to Honolulu. And, yeah, so Hawaii's been my home ever since, except for going to school. I went to school for a few years in San Francisco, went to Pratt in New York.

Did a two year artist in residency in Ohio. But except for the Navy and my travels and that Mexico trip. After that I guess all the travels that drained the travel bug from me so I didn't do that much traveling until I started getting assignments, to go to Micronesia, different parts of the Pacific which would have been probably in the 90s, in the 90s and early 2000s.

Leafbox:

So tell me about your, your first kind of photography is. I guess I would call it political photography. And then you shift to this kind of underwater photography. And then in between you have a kind of a travel photography period. What explains your shift away? Are you going back to politics or do you continue, do you see your underwater photography as political or environmental or what's the thematic arc?

Wayne Levin:

Actually, when I moved to Hawaii, I got really hooked on body surfing and then bodyboarding. And I love that. I'd, go to my favorite spots. My favorite spot was Makapu'u. And And I would spend hours and hours there. And so I really loved that. And also I'd go to see surf movies and watching that.

And I noticed [00:22:00] that a lot, a one standard shot. that they'd use in surf movies, which they would film the approaching surfboard above water. And then as the surfboard passed, this photographer was in the water he ducked under the wave and get the skeg of the board and the churning wave from underwater.

And I was thinking, oh, I could do that with still photography. So anyway I was, When I graduated from Pratt, I got a teaching job at University of Hawaii, and as a coming home present, I decided to get myself for underwater camera, and I started a little bit. To photograph the surfers from underwater.

I started using color film and everything was blue on blue and very murky. I decided to try black and white because I was much more adept at black and white photography and black and white [00:23:00] darkroom work and felt like I can control the images more. Added also that kind of abstraction to the picture in that breaking waves from underwater looked a lot like clouds in the sky.

And you see these surfers that you didn't know if they were yeah, and in color, it was obvious that the, it was obvious that they were underwater. But in black and white, it was like, are they, underwater, or are they flying through clouds? So that dichotomy I think really enhanced the work.

So switching to black and white was what really made that work work. And and then when I got this artist in residency in Ohio, of course, I stopped doing underwater photography for a number of years, but when I moved back to Kona I went, a friend of mine said, Oh, these dolphins, there's dolphins in Kealakakua Bay, which was right below where I live.

So he said, you should [00:24:00] photograph them. And I took him up on the challenge and started photographing dolphins and that led to photographing all kinds of fish. Animals and all kinds of things from underwater.

Leafbox:

What made you move from why did you move to the Big Island?

Wayne Levin:

Oh, to the Big Island?

My, to be honest, my parents had a house there. They had built this house in Kona to retire. My but after a year living there, my dad realized he couldn't. stand retirement and moved back to Honolulu and was just using the house as a vacation house. And I decided I asked them if it's okay if I move into that house.

After, I wanted to move back to, rural Hawaii, like the land really rural part of Hawaii. Moving into that Kona house seemed like a perfect solution for me. When I moved back my, I got married to my then [00:25:00] girlfriend, and we, Moved to Kona.

Leafbox:

And then what drew you to the just the country?

What's so special about the country in Hawaii?, why do you like the country versus the city? Why do you prefer the rural Hawaii?

Wayne Levin:

It's easier going. I feel, actually, I've lived a lot in the city. I think at that time, I lived mostly in cities. I lived in New York, San Francisco, Honolulu and then even Dayton in Ohio, where I was living, was a city. I think I wanted to change more.

We have an acre of land, which is a lot of work, because it's primarily jungle. We grow bananas, we get, citrus, and we have a vegetable garden. But it's a lot of work, but I guess it keeps me in decent shape at my age between that and the ocean. Also the, and Kona is the ocean is really nice.

[00:26:00] It's it's not great for surfing, but it's great for diving. So that's, I think the ocean is, and the way the ocean is in Kona is what kept me here. But I have spent a lot of time in Honolulu and I just recently, up until a year and a half ago, we had spent five years back in Honolulu taking care of my mother.

Leafbox:

And then tell me about your projects on Molokai and Kaho`olawe.

Wayne Levin:

Oh, okay. I had this was, In 1983, I was really in the heart of photographing these body surfers in early 1984, and some lady contacted me and wanted me to photograph her condominium. Okay, at the time, I'd do anything for a job, so I photographed her condominium, and she had just been to Kalaupapa, and she said, Oh, you should photograph Kalaupapa.

That would be a really good project. And I said, Nah, I'm into surf [00:27:00] Photography, and I'm not that interested. But then I thought about it a little more and realized that this was a time, this was 1984, and it was a time in Kalaupapa's history where it was still an active community, and I, knew that wasn't going to last much longer.

And then she set up a meeting with me Anwie, who her father was a doctor who specialized in Hansen's disease and spent a lot of time in about Kalaupapa , but she would have Become a historian and was doing over a hundred hours of videotaped oral histories and call it of Kalaupapa and she invited me to come With her and Gene Balbach, videographer she was working with, and go to Kalaupapa and take still photographs.

So I I took her up on it, and When when the first time I used a 35 millimeter, but after that I'd take trips and I'd take my four by five view camera, which is a big camera that uses bellows and the, it's four inch by five inch film that you put in. You have use a dark cloth to over your head to focus.

It's kinda like an old time camera, but it's very high quality and it also is very slow, which. I think got me more into the slow pace of Kalaupapa compared to the Zoomie surf photography I'd been doing, so it's a huge change and it, and I felt it was like a really, an opportunity to do a really important documentary project of of this still thriving society, but in its last days,

Leafbox:

And then for people who aren't from Hawaii, can you just quickly summarize, it's the community for [00:29:00] Hansen's disease, but how many people were there?

Yeah, what was the community like? What was the town like?

Wayne Levin:

At the at its peak, there were, I think, close to a thousand people. And its peak was the early, the very early 20th century. But at this time, it was down to about a hundred patients left. But it was still a very active community. It was very laid back and it's beautiful.

If you Kalaupapa is a peninsula surrounded on three sides. Very rough ocean and I'm one side by 2000 foot cliffs. And I remember, being in Kalaupapa, I'm looking up at the cliffs and sometimes you'd see tiny figures at the top of the cliffs looking down at us. And you really got the sense of isolation that people had must have had there, because I felt I was at the bottom of well, looking up at [00:30:00] the rest of the world up, up above, but on the other hand, it was very beautiful.

And I think after they had come out with the sulfone drugs which didn't cure it didn't cure Hansen's disease, but it left it non communicable. If you were taking these drugs, and it also arrested the progress of the disease. I think 1965, I'm not sure the exact date, but around then patients were allowed to leave and reenter.

Mainstream society, but most of them opted to stay in Kalaupapa because it was a really nice little community and a nice lifestyle. Nowadays, the patients are almost gone. I think it's less than a half dozen left and it's become more of a national park and it's pretty much the residents where before it was [00:31:00] really focused on the patients now seems to be focused more on the park employees, with just a few, just very few patients left.

Leafbox:

How did you approach the sensitive topic as a documentarian? How did you integrate or shoot people?

Wayne Levin:

To photo, a lot of it was photographing the place and not the people, but so in the beginning I photographed I didn't do very many portraits or photographs of people. And. It wasn't the way I was photographing.

It wasn't possible to take grab shots of people who weren't aware of being photographed. So with the four by five camera, it had to it had to be a, back and forth experience. And not only that it was illegal to photograph people without written permission. Their written consent.

[00:32:00] So I had to ask permission. And usually they give it to me more, as they got to know me. So I'd have to ask permission, have them fill out a model release, which was a very limited model release. It was only to use the work for a exhibition I would do and for a book that I was hoping to publish.

But I could, I still like. Can't I wouldn't want to when I can't use the photographs in other ways for instance, I'll have in my retrospective show, I'm going to have Kalaupapa pictures and a number of portraits, but they won't be for sale.

Leafbox:

And then looking back on the project, how did it affect you personally or professionally?

Wayne Levin:

Oh, looking back on the it was. One project that I did, professionally, it was a project that I did that wasn't it wasn't a money making project because basically I couldn't sell the [00:33:00] prints. It was a project just for the experience and for being able to produce that work and to show people, what Kalaupapa was really like and what he And we had quotes with the photographs, which were from Anwei's oral histories.

So they got to, Hear the words or see the words of of the patients also, to get a sense of the place and to get a sense of the humanity of, people who happen to have Hansen's disease and who had lived most of their lives in isolation because of it.

Leafbox:

And could you tell me about your other work on the Kaho`olawe documentation?

Wayne Levin:

When I, one thing when I went to when I did the artist in residency at Ohio, at the Dayton Art Institute, I decided to do a project on Hospice of Dayton, which was [00:34:00] the at that time it was the second largest. Hospice in terms of patient load in the country, and it was actually the largest in the area that they served.

They, at the time that I photographed, they didn't have an actual inpatient unit. They didn't have the actual hospice building, but they had A few a few units in a in one of the hospitals, but most of it was in in the patients living facilities in their homes. So it was So I got to go with the hospice workers, which were either nurses, social workers, or home health care workers.

And I, you, in most cases, go to the patient's home and, photograph. Basically, it was the relationship between the hospice [00:35:00] workers and the family members and the patients. When I had, at the time that I exhibited the work at the end of the project I had a statement which was if I can remember correctly, it was something like I originally did this, became involved in hospice because I thought the big issue facing us all was the issues of death and dying.

But as I became more involved, I realized that the issue, the big issue was intimacy, which is what I really learned from that project.

Leafbox:

Fascinating. And then, could you tell me about your other Hawaiian work on documenting Kaho`olawe?

Wayne Levin:

Yeah I remember David Ulrich who had he came from Boston and got a position of, Heading up the Hui No'eau in Maui, [00:36:00] and as his first show, he did a show with me and his work.

And I remember him driving me around Maui and talking about, oh, we'd like to do a project on Kaho'olawe. But later Barbara Pope, who I'd worked with previously, With good friend. Barbara Pope is a is probably considered the top book designer in Hawaii. And Maile Meyer, who had a store, Beautiful Things, which really focused on, Hawaiian artworks. They got together and started, decided to publish a book on Kaho'olawe. So they invited four photographers, me and David Ulrich.

And Franco Salmoiraghi, who had photographed Kaho'olawe during the early days of the movement to protest the [00:37:00] bombing of Kaho'olawe. So he had a history of photographs on Kaho'olawe. And Roland Reeves, who was a photographer, but also, primarily an archaeologist and I think he had previously done work on Kaho'olawe so the four of us were the photographers and we we went there to we went there.

I remember they sent me alone on the first trip, and I brought my four by five camera and was photographing color film. I wanted. To capture the spirituality of the island, I think that was my focus. So I was photographing a lot of the old heiau's and a lot owed fishing koas the landscape too anyway, we took numerous trips there to a couple different locations and then we traveled.

Lele, Punauu Heiau, Hawaii, 1993

We [00:38:00] had to travel with military people when we traveled. Across the island because of the munitions that were still there in the earth.

Leafbox:

How was your relationship as a veteran going to that island?

Wayne Levin:

Oh, that was interesting. I think I was not interested at all in the military aspect of the island.

And the other photographers were. That was interesting. Maybe I think I felt because I'd been through all that, that

that this whole military side of Kaho'olawe didn't interest me at all, but the other three photographers were fascinated, I felt with it and if you look at the photography, They had a lot more photographs of the munitions, the unexploded munitions laying on the ground in places and that kind of thing.

But maybe it was because of my previous military experience, but, that whole aspect, I wasn't interested in and it turned me [00:39:00] off.

Leafbox:

No, I just wonder if you felt like how the military treated the island, I think for people who aren't familiar is. It's an interesting aspect as yourself as part of the Navy.

Wayne Levin:

Yeah, no, I felt that. The island was really abused by the military and destroyed. It wasn't only the military that destroyed the island, though, it was like 200 years ago, Vancouver went to, Kaho'olawe and thought it would be a good idea to introduce goats to the island. And they defoliated the island.

They also had cattle ranches which helped defoliate the island. And I read, this seems impossible, but I read that Kaho`olawe has lost an average of two meters of topsoil over the whole island. And it is like really heavily eroded. Yes between the erosion, the overgrazing, and the [00:40:00] explosives it's really been a mistreated island.

And, I know that now the Hawaiians are trying to bring it back to life.

Leafbox:

So Wayne, maybe going back to how, after that work, You've taught photography. What can what lessons you have for other people who are photographers or how do you teach photography or what can people learn from documentation?

Wayne Levin:

Yeah, first of all, I feel a lot of art is basically about communication. With photography and all art, what you, to me the, what you really want to do is what I want to do is to communicate something, the feeling and an idea that's within me to somebody else. And and, as an artist, my, my job is putting it out there, how they interpret it is their, is their Kuleana, it's their idea.

So [00:41:00] I have pretty deep ideas about the work that I do sometimes I write about it, although I don't consider myself a good writer, but I think I have good ideas. So I write about, I'll write about the ideas, but how somebody else interprets it is, then bringing their life experience to it, and it could be totally different from what I see in it.

Leafbox:

And then what are the themes you're most actively trying to communicate now.

Wayne Levin:

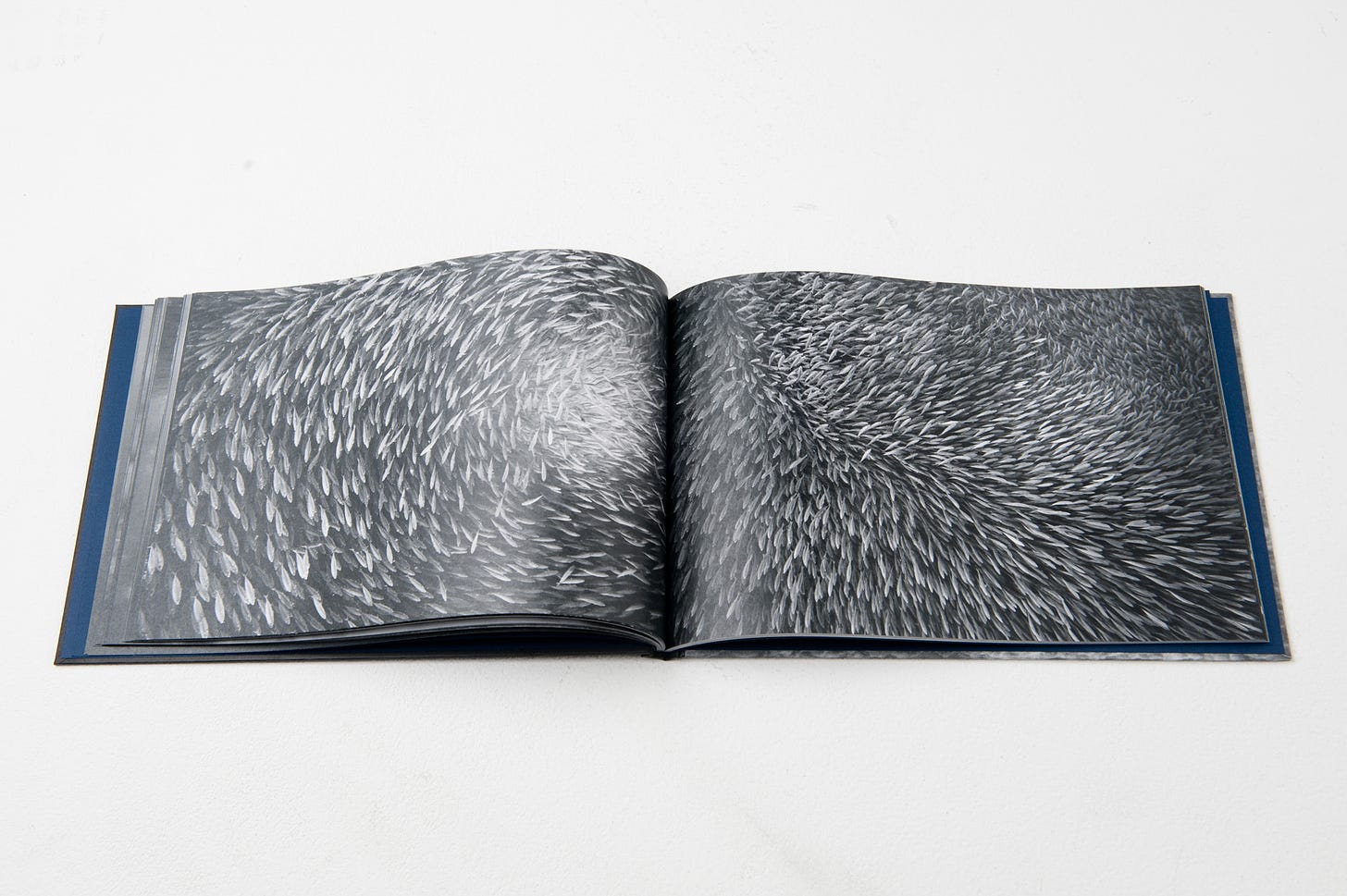

Yeah. And in the past 20 years, 20 plus years, I, to me, maybe the most important idea was what stemmed from my work of the Akule fish schools so in the Around 2000, around the year 2000, I, be, would be swimming out in Kealakekua Bay to photograph dolphins or whatever I see, and I saw what looked like, at first it looked like a big coral head underwater, but as I got closer, I could [00:42:00] see the movement in it, and it was a giant, really tightly packed fish school.

So on my way to photograph the dolphins or whatever, I dive down and take a few pictures of these fish school. And at first I didn't know what kind of fish. It took me a while to learn that it was Akule schools. And then at some point I decided, I realized that these schools were more interesting as a photographic subject to me than the dolphins

So I started really focusing on the Akule schools. And, I dived down I dived down off and turned away from the school. So I didn't. Startle them and slowly I'd turn toward the school and instead of swimming away, they'd swim toward me and they'd be going, they wouldn't hit me, but they'd be within a foot, thousands of fish going by my head.

And it, first of all, that, made me think, okay, that's a [00:43:00] survival tactic that rather than fleeing from a predator, they would confuse them, like it was so visually confusing to have that many, individual fish going by you. But then as I observed them more I was thinking that their movements the shapes they'd make and the way they'd move was like a single being, and I was thinking what's really the individual, what's the individual?

Is it the school or is it each individual fish? And I thought maybe the individual is really the school and the individual fish are more like a cell within a larger entity, within a larger being. And then taking that to other other life forms, I started photographing bird flocks. But then ultimately, and I haven't really pursued this.

Photographically, I'd like to, but humanity, are we [00:44:00] really as our society would have us believe, are we individual entities who's being ends at the surface of my skin, or am I part of something larger humanity, or even. Larger than that, you could take it to the earth. Are we, just a part of the earth?

So it became this project, which has gone on. I'm doing less of it these days, but it's gone on for over 20 years is taking photographs related to the question of what's the individual. So that, that's one idea.

Leafbox:

So Wayne, have you answered that question for yourself?

Wayne Levin:

No. I don't know, I don't know if humanity has the ability to give a definitive answer to that question.

Leafbox:

Do you have a religious practice? Spiritual practice. I'm sorry? Do you have a religious or spiritual practice?

Wayne Levin:

A little [00:45:00] bit. I my, I guess my spiritual philosophy stems from that same idea and that, if there's a, it's if the earth has a consciousness. Which would be comprised of the consciousness of all the living beings on it as a single consciousness or as a combined consciousness, then to us individuals that would be God. So to me, my philosophy is there is a God and it's the earth, but then for the earth, there's probably a God and that would be the solar system.

And to the solar system, it would be the, the galaxy and so on, so whatever you're a part of would be your God, I would think. That's my spirituality. And it really It combines with that, with the idea that I got from photographing [00:46:00] Akule.

Leafbox:

And then one of my last questions is shooting in Hawaii, how do you consider yourself local or are you still a visitor or what's your relationship? Do you consider yourself local or are you still a visitor? What's your relationship to Hawaii in general? You've shot so much of it. Are you still learning?

Wayne Levin:

Yeah. My relationship to Hawaii. Yeah, I feel like I'm, I've been here a long time, but I'm still a visitor.

I, I obviously, I really love Hawaii. I hope it could, not be spoiled too much in, in today's world, I don't I don't know how I feel about, the huge influx of tourism but yeah, I feel pretty connected to Hawaii as far as the Hawaiian movement. I support it, but I don't feel as a, how the part of it, but my photographs I feel like my photographs supportive, support the Hawaiian movement.

Leafbox:

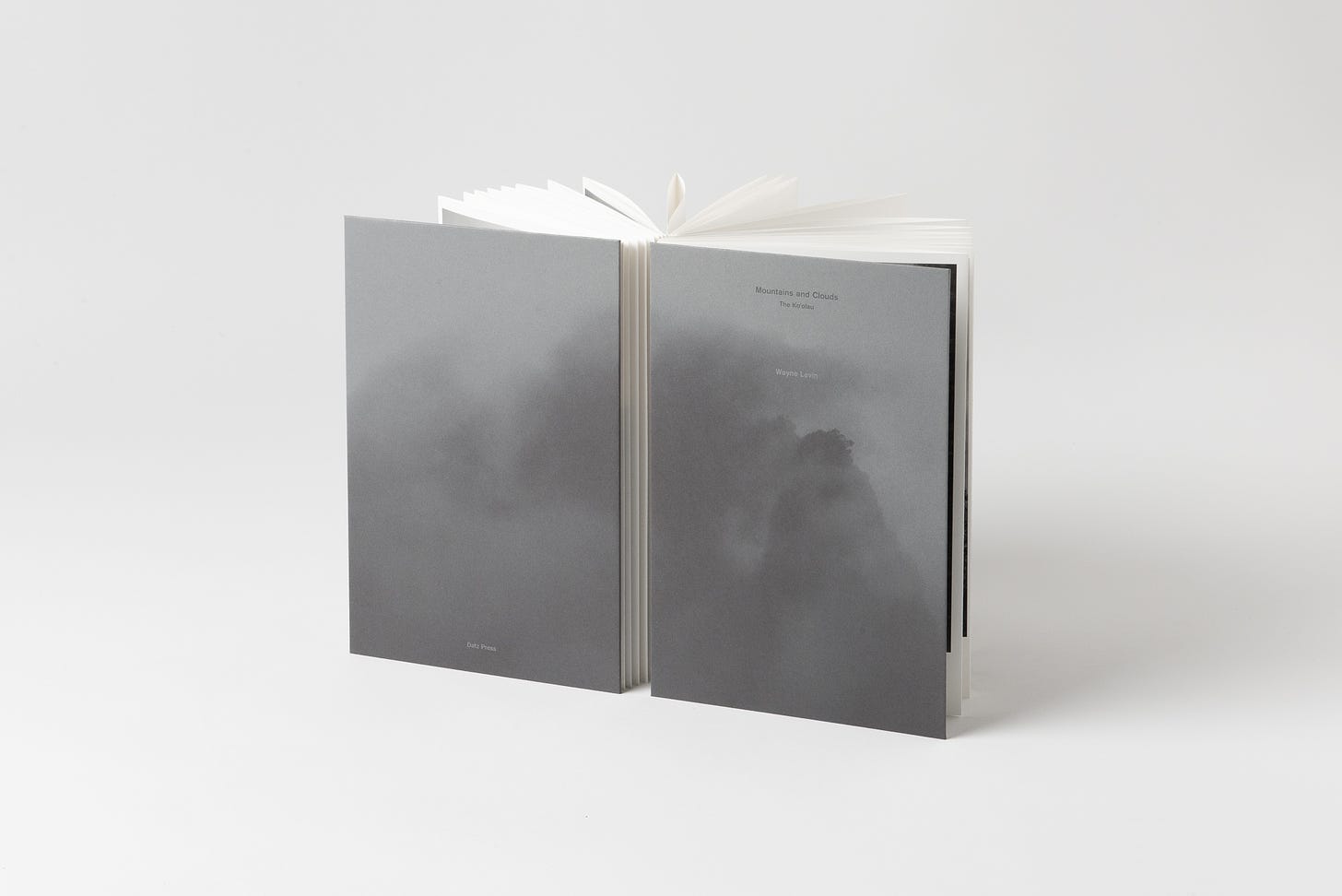

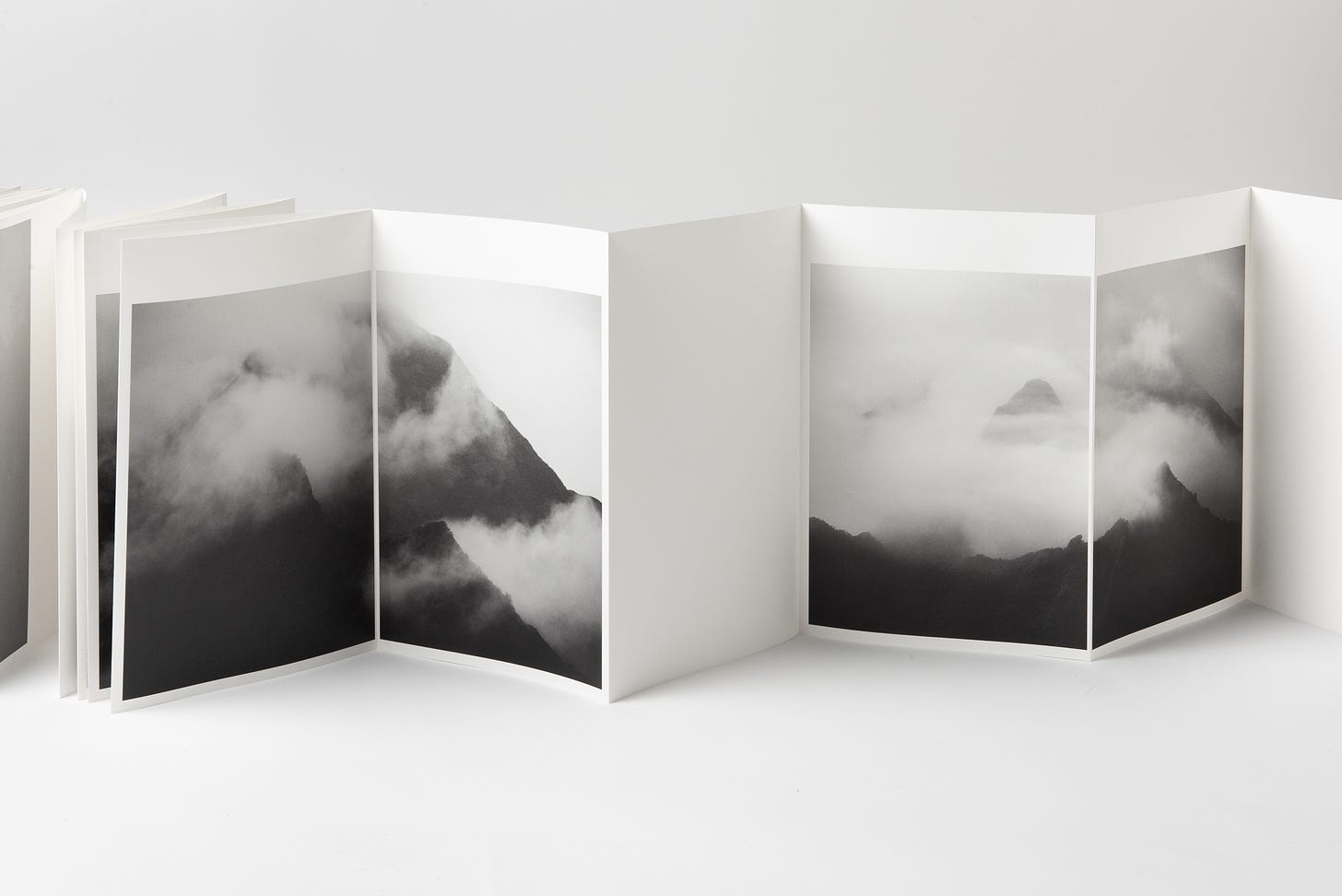

And then your latest book, [00:47:00] The Mountains and Clouds, how did you shoot that book? And how did you approach moving from the ocean to the sky?

Wayne Levin:

Okay. That book.

We moved to Oahu for my daughter's education. We didn't feel the schools around here were too good. So we moved to Oahu, she, and she ended up going to La Pietra, but when we first moved there, we stayed at a friend's house who lived in Haiku Valley, and I'd watch the clouds wrap around the Ko`olaus, and, I was really drawn to it, and it, I think, stems from my love of Asian scroll painting so I slowly over, maybe seven, eight years, I started photographing the Ko`olaus whenever I'm on Oahu and I'm only interested in it with when the clouds wrap around it.

So I'm really [00:48:00] interested in that relationship between the solid matter of the mountain and the more visceral form of the clouds. And I'm, I've been really influenced by Asian scroll painting and especially the one, the theme that they often use, which is mountains and clouds. So when I had all my work together and I felt like it was time to publish a book I had worked with a Korean publisher called Datz Press.

So I went, I thought they would really understand what I was doing. So I went to that press and showed them the work, and they really did understand, and especially they understood the the relationship with it. Asian art. So the way that they printed the book, a lot of the horizontal pictures were divided by gutters into individual [00:49:00] verticals.

So it'd be a big horizontal, be it divided into two or three vertical pictures. And when I first saw it, I was going, oh, that, I don't know if I like that. And I questioned that. And then they sent me this beautiful picture of a screen painting, where it's in three parts, this Beautiful landscape.

And it's divided. It's three screens then I understood what they were doing. I was really lucky to find a publisher that really appreciated and understood even beyond maybe my understanding of what I was doing. They did a beautiful job.

Leafbox:

Are there any other projects you're working on now that you'd like to share?

Wayne Levin:

Yeah yeah, my current project I'm working on, I'm continuing some of my older projects, but the current project, I called The Edge, and it's photographs of the meeting place between land, ocean, and air. This project has [00:50:00] its roots in my very earliest underwater photography because when my parents, back in the early 70s, when my parents moved to the Big Island, we'd go to Honaunau Bay snorkeling.

From the Edge

Now it's like totally You know, crowded, but we would be the only people on the beach and I go snorkeling and I was mesmerized by how beautiful it looked along the reef when the waves were breaking on the reef and then draining back into the ocean. And I wanted to photograph that, so I borrowed a friend's underwater camera and I got swept over the reef and scratched his lens, and he said, okay, you bought the camera.

That was my first underwater camera and I tried photographing it, with this underwater camera using, color film and it just didn't work. It just didn't come out good so I never pursued it, and then Like a year and a half ago, I finally got a [00:51:00] a really good underwater housing for my digital camera.

And I was just going out snorkeling, taking some pictures with it. And I took a few of the shoreline. And I went, wow, this is really capturing the color and the feeling that I was trying to get 50 years ago. So I started a project, concentrating on that, what I called the edge, photographing just that meeting place of the, where the water meets.

The land and the air, and I had my, I had a show there that just closed a week ago at the Lo`i Gallery in Honolulu. And some of that work, that'll be the most recent work at the retrospective show.

The retrospective show I haven't announced. So it's at the Downtown Arts Center on Nu`uanu Street and it [00:52:00] opens July 25th to August 31st and the opening, there'll be a big opening on the first Friday, which I believe is August 2nd.

Anybody who's interested is welcome to come to that and I'll be there. And it's been a huge undertaking. To, it's a very large space, and I have about 160 pieces in it, so it's been like overwhelming, but it's been wonderful to be able to go through my, all my past work, and, bring it back, work that I'd almost forgotten about, and bring that back.

But also, there's a lot of focus on my underwater work, which is mostly in the last 25 years. For me, 25 years is like yesterday. Yeah,

Leafbox:

Yeah, I think some of your Akule, the pyramids are amazing. So yeah, include some of those. Wayne, is there anything else you'd like to share? I'm very excited about your retrospective show.

Wayne Levin: [00:53:00]

No, I think that's good. If you have any more questions, feel free to ask.

Leafbox:

My only last question is you work. What's the role of you've worked with Tom Farber, but And all these other photographers. How do you approach collaboration? Or how do you see that versus your solo work? What's the difference?

Or do you like collaborating or not?

Wayne Levin:

Yeah, I like collaborating. Like I when they invite, invited me to do this show at the Lo`i Gallery I was already, working almost a full time job on this retrospective show, so I felt like it was too much for me to do a one person show, so I invited a friend and a good photographer from the Big Island, Val Kim, to exhibit with me.

And then we're thinking about doing or planning to do a zine of that work. I'm collaborating with that, I've collaborated on a lot of projects, but I guess I would call myself [00:54:00] basically a loner. I'm very comfortable working alone, but when it's the right combination, I really enjoy collaborating.

I've always enjoyed working with Tom. And guys, I've worked with some other writers. Yeah, so I could go. I could work either way. I'm pretty flexible.

Leafbox:

And then my last question is just as a photographer in communicating. No, my question would be. Where do you get that internal drive? Where is that desire for, is it a self exploration or are you trying to communicate something? Or where is that desire to keep going in your artistic practice?

Wayne Levin:

I think you hit it pretty much. The two driving forces is exploration and communication.

So for me to something that I'm drawn to and explore it deeper and I do have a strong. Political side. Sometimes I could get into that. Oh, another series that I didn't speak of that'll be in the [00:55:00] show is On the Wall. I would, the wall that divides the U. S. and Mexico. So I did, I the way that came about is I when Trump was elected in 2016, I joined a Resist Trump group.

But this group focused mostly on immigration, on the immigration issue. So I became really aware of, how inhumanely we were treating people who wanted to immigrate to America. And I so I decided I wanted to do a project, some, relating to that. And I decided to photograph the wall, but I wanted to relate it to my ocean work.

So I did, I titled this project, Where Borders Cross. And it was, I focused on the crossing point between the natural border between the American continent [00:56:00] and the Pacific Ocean, and where it crosses the man made border between U. S. and Mexico. It was I went to this town. I wanted to photograph both sides of the border, but at that point.

The U. S. side of the border was closed because of flooding so I couldn't photograph that side, but I photographed from the Mexican side and it, the, while, I knew before I came here, Went there by looking at pictures that the wall was covered with artwork, artwork and graffiti. So I thought it was really fascinating on the way that they constructed the wall.

They wanted to be able to see what was happening on the other side. So they, there'd be these about four inch steel posts with about another four inches space in between each post. So I always liked. To work with the idea of conflicting realities, so photographing these posts, which were [00:57:00] covered with artwork and graffiti, and then you'd see through them to whatever's behind.

which would vary, it would be sometimes a really beautiful beach on the U. S. side, but also a secondary fence, and now they're building a secondary wall, 30 foot wall, I think about 50 feet into the U. S. side of the border, but at that time it was a big chain link fence with lots of barbed wire. So anyway yeah, that was the Project I wanted an opportunity to speak about.

But then, so to me

Leafbox:

Wayne, when you saw the border, did you, are you a pro open borders person or did you mean Hawaii has a very complex relationship with immigration?

Wayne Levin:

Yeah,

Leafbox:

I'm just curious.

Wayne Levin:

Yeah I don't know if I'm actually pro totally open borders, but I'm pro being more humane to, and to people [00:58:00] who are migrating because their living conditions in their country is so unbearable, and they think that they could get a, have a better life in the U.

S. I don't feel that they're criminals, but and I feel that they should have a chance, to be able to immigrate to the US. I think, I really think that the fear of immigrants is way overblown. And, I don't think very many people who are terrified of immigrants have actually had a experience and negative experience because of immigrants.

And I think You know, a lot of them are doing, are working in jobs that, frankly U. S. citizens don't want to do so there's even an economic reason to allow people in Yeah so anyway, I just believe in having a more humane, we're a nation of immigrants, we're [00:59:00] all immigrants, basically, we've all, if you go back in any, even Hawaiian history, if you go back far enough, we've all come from somewhere else.

Leafbox:

Yeah, it's a very complex topic. I personally think My more libertarian thinking living in Hawaii, you start. Yeah, I don't know if open borders really work in Hawaii. Oh, yeah. Yeah, very complex topic, right? Yeah, it's a very complicated topic. I was just curious if your thoughts approaching the US border and the last four years have really,

Wayne Levin:

Yeah, I don't think they should be totally open, but I think that I think that we should have a more humane process of working with people who wish to immigrate.

Leafbox:

As you grow older, I think one of the topics Tom has really approached in his writing work is the aging. How do you feel about aging as you?

Wayne Levin:

I, I feel pretty good as far [01:00:00] as my health and being able to do what I want at 78, which is lucky but I feel, I realize my time is limited yeah, I don't think I'm going to live forever, but so I feel my time is limited.

It makes the retrospective show really important for me and yet, like yesterday, I went out and, took some really interesting photographs and I know it can't be in the show at this point. We can't be adding more work. So that's I was joking with my wife is that this could be my post mortem photography, but, like the retrospective show is my life's work. So what do I do after that?

Leafbox:

What were you shooting that was interesting recently?

Wayne Levin:

I went to I won't name where I went. But it has beautiful sand patterns and it was pretty rough.

So there were all these clouds kicked up by by the [01:01:00] waves. So it's basically photographing underwater seascapes which were these beautiful sand patterns and these Clouds, the sand clouds that were kicked up. And then in some cases, lately, I've been really into photographing schools of tiny little fish, like an inch or shorter.

And, there were a lot of those I was photographing that as well. It was more place oriented. If I expand on this project, it'll be it'll be a project on that particular place, which is I was thinking of the word, wonderland, because I wasn't sure if I wanted to name, which beach it actually was.

Leafbox:

And then, Wayne, curious what your daily schedule of a photographer is like. Do you wake up? Do you shoot in the morning? Do you approach each day differently? Do you have a set routine?

Wayne Levin:

Yeah I don't, I would say I [01:02:00] photograph in the ocean. Lately I've been so busy with the, with this show and other things that in our garden.

That I've probably been averaging two days a week in the ocean. But on those days, I normally, I want the sun higher. So I normally go out in the late morning, maybe 10 or 11. So I'll get up, have a leisurely breakfast, go on the computer and then then mostly down to the ocean. And either do a snorkel or a scuba dive, depending on where I go and what I want to photograph.

More lately, I've been doing more snorkeling. In the past, I've been more scuba diving, lately snorkeling. With this project, The Edge there's a lot of surge. Sometimes I do get carried over a shallow reef. After getting cut up a bit, I decided, I was told, you should wear a wetsuit.

And I thought, oh yeah, that's a good idea. Why didn't I think of that? So [01:03:00] now I wear a wetsuit, which it makes me very buoyant and it protects me. It makes it really hard to dive down, because I'm so buoyant with the wetsuit. But yeah, anyway, it's pretty action photography. Photography and when the surge takes you in over a reef, you're helpless.

You have to be really careful.

Leafbox:

Has any of your relationship to the ocean changed? Some people fear changes, with an experience or sometimes, I surf and sometimes, a big wave will shock you for a week or something sharp.

Wayne Levin:

Let me think I have to think about this.

I think it's essentially pretty much the same. It, from the days when I, And, when I was first doing the underwater work of surfers, which is what really got me, it was really the beginning of my serious underwater photography it was really a conflict each day on whether I wanted to go out surfing or photographing.

And [01:04:00] I remember asking a girlfriend I had at the time, what I should do. And she said, Oh, you should photograph. But I, but surfing was more fun. But nowadays it's pretty much, there's not that question. It's, I go to the ocean to photograph. Yeah, so that's changed, and over time that it, that I very rarely go for just recreational purposes.

I, when I go to the ocean, it's business, I don't hang out on the beach. My dermatologist is happy about that. And I just get my gear together, put it on, get in the water, and when I come out. I get my stuff in the car and go back home.

Leafbox:

And is there any music you particularly like that?

Wayne Levin:

Oh, music that I really like. I'll I don't know if it still works with my work when I, in the past, when I was when I did slide shows, sometimes I would do it to the [01:05:00] background of Martha Argerich playing there's, my French pronunciation probably isn't good, but gaspard de la nuit, the second, no, the first part is called Ondine. And it's about water spirits. It depends on the work, but I have used that.

And so that's Ravel, and there was another Ravel. Ravel's Piano Concerto. I think one of the movements seemed to go really well with water.

Thank you.

More @ Waynelevinimages.com