Interview: Linh Dinh

Linh Dinh a Vietnamese-American writer, translator, and photographer.

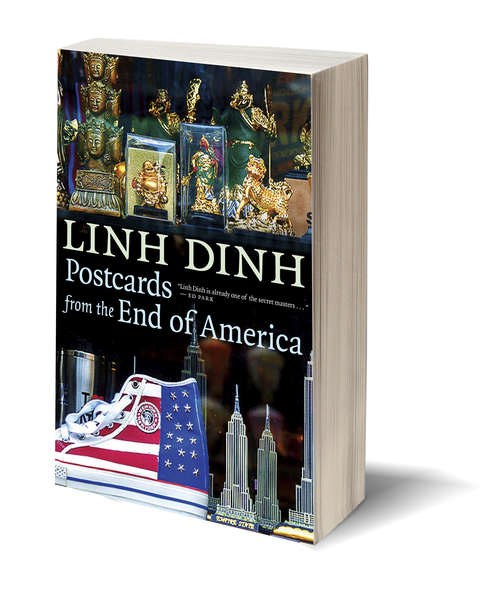

Linh Dinh is a Vietnamese-American poet, fiction writer, translator, and photographer who I first discovered watching an interview with Chris Hedges discussing the plight of the underclass. Linh's lastest collection on the US, Post Cards from the End of America is a roaming encounter with America's, the West's and contemporary people's financial, political, persona. challenges. Mixed with humor, optimism we connected to discuss chasing COVID, how to travel, censorship in Vietnam, collapse, on being a loser, carpe diem and other Ờ-mây-zing! topics.

All photos copyright Linh Dinh

Leafbox:

Even though you write about collapse and people on the out, there's something always positive which I appreciate. I wanted to know where do you get that positivity from?

Linh Dinh:

Though I've talked about ethnic, racial and national differences, which you can’t help but notice when traveling, I don't have problems getting along with people as individuals, so that's the positivity, I suppose. Plus, it’s not wise to be an asshole in an alien environment, or you might end up dead, or locked up with twenty stinking gentlemen you can’t communicate with. Would you mind not splattering urine on my head when I’m sleeping?

Even in the US, I was often clearly an outsider, so this shaped my behavior. Taking the Greyhound, MegaBus or Amtrak across the country, I’d get off at some place I knew next to nothing about, so I’d just walk and walk, until I hit some lowlife bar, because that’s where I could meet people and afford many drinks. I was essentially home.

Generally, I don’t overly research a place I’m about to visit. I don’t even want to see photos of it. This ignorance enhances my surprise, even shock, when I get there, though surprises are inevitable, no matter how much research you’ve done. Although I spent three decades in Philadelphia, it continually surprised me, when it didn’t bore me to death, that is. All places are infinite.

In any shit bar, almost without fail somebody would talk to me and, before I knew it, I had learnt about his work history, present job, sexual habits, hope and fear. In a Woodbury, NJ dive where folks downed Bloody Marys with their breakfast scrapple, a frazzled stranger lamented to me about his torturous work schedule, with day and night shifts all mixed up, so he could never sleep properly. Not everyone finds that interesting or enlightening, but I can never get enough of how we get by, so I listen, and not just to what is said, but its delivery. I marvel at each man’s diction and cadence, so I can steal his language, of course, with gratitude.

In a country where I don't speak the language, I can't do that, obviously, but you can learn a lot by just looking at people.

I just got back to Vietnam five months ago. Because of COVID, I was stuck outside for 2 years. I had never traveled for such an extended time, drifting from country to country. Plus, without much money, it wasn't like I had the option of traveling much. When I was well received as a writer, I would get invited to give readings, but they would fly me in, pay me, then I would fly out, so many brief visits to many places. Once, I was hosted in Marfa, Texas for two months, but that was highly unusual. When I traveled on my own, I would often sleep on a bus or train to save money. I couldn't afford hotels really.

For 2 years, I stayed in eight countries. But you know how it is, man, if you stay away from Europe, you can find cheap accommodation. Even in Europe, there are some cheap places, so I was paying less than I would have if I was in Philadelphia.

Leafbox:

You said the word alien when you entered the US and let's say you enter a new bar, what's your modus operandi? What's your first question you ask someone? I'm curious how you approach strangers.

Linh Dinh:

Well, I just sit down. You can tell when people want to talk and, usually, they do, and most people are pretty friendly. Sometimes, though, they’re preoccupied or talking to friends, so I just sit and watch. I'm very comfortable in dives because those were my social spaces in Philadelphia anyway. Because of my budget, I couldn't afford anything else. In Cape Town, for example, I went into Corner Bar in Sea Point and, just like that, I was talking to people. A beefy black guy joked that I looked like a Kung Fu master, then a white man told me his wife had died from COVID. Although I was in Africa, the place felt familiar to me. In Windhoek, Namibia, I stumbled onto The Old Location, so I just chattered away, but mostly, I listened.

I go to where people are. In the US, people don't hang out in many places except for crappy bars. In Vietnam, it's a little easier to mingle because there's all these cafes and restaurants, and people spend a lot of time on sidewalks. In Vietnam, I don't have to go to dive bars, but there are no dives anyway. There are bars for Westerners, but Vietnamese don't have the habit of going into bars to sit on high stools and drink alone. Usually, they eat as they drink, with friends. In Vietnam, I can just go to a café and overhear conversations. I also get a lot of information that way.

Leafbox:

What is your usual drink of choice?

Linh Dinh:

Just beer, man. I rarely drink hard stuff because I don’t want to get wasted too quickly. With beer, I can drink for hours and still be coherent. At home, I rarely drink. I’m a social drinker. I enjoy looking at people, hearing people and I find everyone interesting.

Leafbox:

When you meet new people do you tell them that you're a writer or do you usually wait to inform them of that?

Linh Dinh:

I rarely tell them. They don't care. I just listen to them. I want them to tell me about themselves and, usually, people are more than eager to talk. Most people aren’t very curious about me, which is fine. I don't care.

Leafbox:

Were you this curious as a child or where did this curiosity first come?

Linh Dinh:

I came to the States when I was 11 and we were very poor, so we didn't really go anywhere. But we did drift around to find a congenial place to settle. My father drove us from Tacoma to Houston, and we stopped in LA to see a friend of his. Our cheap car, a Chevette, broke down in Arizona. After two months in Texas, we decided we wanted to return to the Pacific Northwest. Taking a different route, we passed through Kansas and Wyoming, etc. I remember seeing thousands of pronghorns. Though I got glimpses of all these places, I was just a child, so had no control over anything. I couldn’t say, "Let's stop here for a few days.” Still, I became very curious about places.

With my first car, I’d drive from Virginia, where I lived with my mother, to DC or Baltimore. When you're that young, though, you really don't know anything and you’re intimidated, so it took me a while to get the hang of just roaming. As an adult in Philadelphia, I would take frequent trips to New York City. Visiting New York was very stimulating, but Philadelphia was more congenial. I found New York, especially Manhattan, to be very pretentious, too much preening and posing, so I grew to dislike it, but Philadelphia felt more authentic, because it wasn’t glamorous. To be overly conscious about your image is a corrosive madness.

Leafbox:

Linh, when you first moved to the United States that was part of the refugee situation with the Vietnamese or what was the reason, economic?

Linh Dinh:

Yeah, I got out just before the airport in Saigon was shut down, because of shelling. Many civilians died. A few hours later and I would have been a corpse. The excitement of going somewhere, though, was what I felt most. It drowned out any fear or anxiety I had.

Leafbox:

Got it. How was the linguistic shock for you as a child?

Linh Dinh:

My father was a lawyer and he was also a minor politician in South Vietnam, so he had these positions. He was also in the police force, as a lieutenant colonel. He had a bit of money, but he wasn't very well educated. He didn’t really know any foreign language. When he got to California, he tried to pass the bar exam, but he just couldn't do it. He was already 44, and that’s just too old to grasp a foreign language to pass a very complicated exam. So anyway, although my father was a lawyer, he wasn't cultured.

He did force me and my little brother to study all of these languages, which was a kind of torture. Even at the time, I thought, "This is very unreasonable." He had me study French, English and Chinese, and that's just too many languages. This, on top of Vietnamese. A child should not be subjected to that. So I resented that very much at the time and I still think back at it with a kind of horror, but perhaps that exposure to all these languages forced me to be more open to learning an alien language.

Leafbox:

Do you have children now or no, Linh?

Linh Dinh:

No, no, no. At a very early point in life, I realized I had to be very careful to get by. I was a painter, and it’s very expensive to maintain a studio. I realized I had to cut out most expenditures just to make it as a person, much less as a painter. I rarely bought anything. I've owned two cars in my life, for a total of maybe a year, which is very unusual. I lived mostly without a car my three decades in the USA as an adult. I hardly bought anything.

I even stopped buying music. I thought, “Wait a second, you can't afford 20 bucks for a CD!" So I cut out many expenditures. Having a child would be out of the question. When I was young, my biggest fear was to be a failure as an artist, which was exactly what happened, but I became a writer. You know how it is, man, you sacrifice so much to do this. The chance of you doing anything, gaining any kind of attention, is very slim. I had a tremendous fear of exerting myself to such a degree, but still end up with nothing.

Leafbox:

And what is your fear now as maybe past middle age and more as an established writer and photographer and artist? What's your biggest fear now?

Linh Dinh:

OK, so after a while, I got published. I think I ended up publishing 10 or 11 books in English, I can't remember, maybe 10 books. Anyway, there was a point where I was treated fairly well, I was invited to places, I was anthologized. I think I got a little sloppy. I've always been impatient. Even now, I'm very impatient with my writing. I crank out a lot. So there was a point where I got a little sloppy. Looking back, I'm like, “Man, you should have spent more time on this poem, or you shouldn’t have written this poem, etc.” As someone nearing 60, I look back at my so-called writing career and see all the missteps. I'm trying to correct them. I just finished editing my Collected Poems.

The book was supposed to be published in the USA before the publisher became appalled… It was all ready to go to the printer, then it got cancelled. Now, I'm going to get it published in Vietnam. I have a publisher here, but it's an underground publisher. It won’t be distributed in bookstores, but it will be a book, and that's all I want. I want a document of all my poems, of all the poems I care to keep. Just going through all these old poems was rather painful, because I had to eliminate a bunch, and reworked a bunch. Sometimes you can just tweak a word here and there. A seemingly minor edit can make a huge difference. Anyway, my Collected Poems is at the publisher and I sure hope this guy doesn't cancel me also! It should be out soon.

Leafbox:

Now that you're back in Vietnam, are you writing in Vietnamese as well?

Linh Dinh:

Well, I compiled two books in Vietnamese, but mostly translated from my English writing. I haven't written directly in Vietnamese in a while. For a short period, I did that while living outside Vietnam. Of these two books, one is of my recent travel writing, originally written in English, now translated by me into Vietnamese. Because these are my pieces, I can take more liberty with the translation. If it was someone else's work, I would have to be more exact. You can't mess with someone else's thoughts or style, you know.

Leafbox:

So Linh going back to language, I'm just curious, as someone who speaks many languages, did you find your Vietnamese had caught up with contemporary Vietnamese after being away from Vietnam for so long?

Linh Dinh:

I speak English and Vietnamese. Since I lived in Italy for two years, I learned to speak very basic Italian, but I'm not really good at languages. I studied French as a child, so I can read shop signs and maybe half of a newspaper article, and I can do the same with Spanish, but I'm not conversational in any languages except two.

Leafbox:

Well, two is more than most Americans.

Linh Dinh:

But I just want to clarify that I don't have any exceptional facility with languages. Anyway, my Vietnamese deteriorated during my time in USA, because I wasn't using it very much, but in 1995 and 1998, I returned to Vietnam, then in '99, I came back and stayed for two and a half year. I've worked at regaining my Vietnamese. Because I’ve translated quite a bit of Vietnamese literature into English, I had to improve my Vietnamese.

Like I said, there was a period when I wrote directly in Vietnamese, and I was surprised I could manage it. I got good responses from leading Vietnamese writers. Although some people still find my Vietnamese a little weird, it’s not because my Vietnamese is bad. It’s because I do certain things stylistically that annoy some people, you know, the more rigid ones, or maybe they’re just slow learners! I’ll teach them!

With my two Vietnamese books coming out, readers will finally get a chance to examine my writing in my own language, because I have been translated rather badly by other people. Until recently, I didn’t realize how distorted or even degraded was my writing in Vietnamese! It’s very important to straighten this out, because I don’t want to die as a clown!

Leafbox:

Nice. Linh, what is the contemporary Vietnamese writing literature community like? Is it all in Hanoi or is it academic? Is it fiction for mass culture? I'm just curious, who is the reader in Vietnam?

Linh Dinh:

After '75, the South Vietnamese writers who got out, they continued to write overseas and there were also new writers emerging, outside Vietnam. It was a very lively scene because there was a lot to talk about. They had endured so much trauma. Although these writers were not allowed to publish inside Vietnam, many of their works got smuggled back in, so there was a very healthy scene outside Vietnam. The problem was these people got older, and the younger generation was not that interested in reading Vietnamese, or even being Vietnamese! So all these Vietnamese bookstores in the USA, France or wherever started to disappear. With writers dying or not much read, this scene has pretty much collapsed. With the internet, these overseas writers can be read inside Vietnam, but most readers have become too flighty or dumbed down to engage with substantial writing.

We see this with every language. Paradoxically, the internet allows people to write and read much more, but they read and write so sloppily, they can’t really grasp anything, and even when they do, they’ll forget it within seconds. People have a hard time recounting what they read online just a minute ago.

The internet, then, has actually hurt writing in every language, so it has hurt Vietnamese writing. Inside Vietnam, serious writers are barely visible. For about 15 years starting in 1989, there was a lot of exciting writing inside Vietnam, because the government had eased censorship considerably. With many writers emerging, there was a lot of excitement, but that has died out. One reason was the government reasserted control, though not as severely as before.

Writers are mostly left alone. For example, my two new books won’t be allowed to be sold in bookstores, but no one will get in trouble. At least I hope not! I have already published two books of poems in Vietnamese, but they’re underground, so the government doesn't care. In the past, it would go after the publisher and maybe even me. Now it doesn’t really care, because no one reads these books anyway. The younger generation is not really interested in serious literature. They’re on Facebook or watching YouTube, so the writing scene here is not very healthy right now. There's also this infatuation with English. In pop songs, you hear English inserted into lyrics, many shop signs flaunt English, often ridiculous, and richer kids go to bilingual schools. All these phenomena mean there is less attention paid to Vietnamese. A deep, sustained love for the language breeds serious literature. When this is largely absent, all you have is a handful of stubborn weirdos composing for almost nobody. With English so purposely degraded, English speaking societies have become madhouses, with inmates manically flinging incoherent shit at each other!

Leafbox:

It's interesting Linh, the American culture is still the hegemonic in Vietnam. Because I read about China and Japan and even Russia seems to have influence into Vietnam. I'm just curious so the American dream is still active.

Linh Dinh:

Here's a sickly funny story. One reason Vietnamese are so vaccinated is that they trust American medicine. I find this sadly hilarious. Although these fuckers showered Agent Orange onto Vietnam, Vietnamese now line up to get maimed or even murdered by Pfizer! When the first batch of Pfizer “vaccines” arrived, most were shipped to Hanoi, so the top Communists and their families could snatch them. Having fought Uncle Sam not that long ago, they still trusted him to bring them health and happiness, and not blood clots, strokes, heart attacks and numerous other illnesses! Save me, Uncle Sam!

Leafbox:

The brand, whereas in the Communist Party in China will never, of course, you can't take any of those shots in China, maybe.

Linh Dinh:

The top Communists here send their kids to schools in the UK and in the USA. Some buy houses in the USA. So enamored of American culture, wealth and glamor, they’re scrambling onto the sinking Titanic. It's hilarious.

Leafbox:

But that just seems like the oligarchic class, in China it's the same. So who is the censorship regime in Vietnam controlled by, is that the middle bureaucrat then?

Linh Dinh:

Listen, they don't want anyone to say anything bad about the Communist Party, it's a big taboo, so you can't question Ho Chi Minh, for example. You can't mock Ho Chi Minh or address corruption in the Communist Party.

Leafbox:

What about religion or LGBT kind stuff is that censured or is that just…

Linh Dinh:

The gay and transsexual scene is not too visible here. It has permeated this culture too, but not like in the West, where it has become nearly a state religion! Vietnam is still very much a traditional society, and it's certainly very nationalistic. The Communists here don't stress Marxism, internationalism or class struggle. They derive their legitimacy by posing or rebranding themselves as nationalists. Even Ho Chi Minh projected himself as a nationalist above all. Communists have to do this because most Vietnamese are merely nationalists. They just take it for granted that Vietnam’s heritage, history, culture and language should be protected. I just said that they're enamored with English, but very few of them can speak it comfortably. I just saw an ad at a convenience store. They use the English “amazing,” but transcribed into Vietnamese.

Leafbox:

No, I get it. It's like loan words in English or Japanese where it adds cachet to the language.

Linh Dinh:

It's retarded. At the top of this help wanted sign is, “Ờ-mây-zing, có job!” So only “have” is in Vietnamese, with “job” and “amazing” in English. Businesses here use English even when they know customers can't even read it. Like you say, it lends cachet to the store. It intimidates people when there's English on the sign.

Leafbox:

So going back to the creative process, if most of the creatives are in the undergrounda and if they just stay away from taboo censored` topics. Basically, they have free reign, it's very libertarian, they can do whatever they want except certain topics.

Linh Dinh:

OK, like sexual content, it's not that big of a deal, but they're not going to have a song that says “suck my dick,” like they do in US. Vietnamese listeners won't put up with that. It's not the government, but the people objecting to that. Civilized people don’t tolerate such cultural pollution.

Leafbox:

It's a conservative society still. I understand.

Linh Dinh:

They just find it appalling. Sometimes I play videos of American music for my friends here, just to show how degraded American culture has become, and they're just shock. They're like, "What the hell is this?”

Leafbox:

Well, let's talk about that degradation. There's a show on HBO in America called The House of Ho, it's kind of a Kim Kardashian reality tv show... have you heard of this?

Linh Dinh:

No, I haven’t.

Leafbox:

It's basically, a reality show on a rich Vietnamese-American family, the wealth they have, their life. They're like Kim Kardashians, they live very extravagant, they have mansions, and it's all about the family battle. But what's more interesting about the show is that it's very popular in Vietnam and maybe they are selling the American Vietnamese dream.

Linh Dinh:

Wow. I didn't know that. I've never heard of this. Ờ-mây-zing!

Leafbox:

I'm curious what the relationship is between Vietnam and American Dream. Is that because the upper class Vietnamese dream about the American dream still is that what the relationship is about? Maybe you can tell me since you are both a Vietnamese American and Vietnamese, what's the relationship between the two?

Linh Dinh:

Most people here still believe in the American dream, they believe USA has to be number one, and there are several reasons for this. Most white people you see here are well off compared to the locals. If you are a poor white person, you're not going to come to Vietnam. Since you can't even fly to Mexico, you're not going to show up in Vietnam. Since whites here tend to throw their money around, most Vietnamese are convinced whites are filthy rich. Also, overseas Vietnamese also throw their money around when they return, the ones who can afford to return. None will admit they can barely pay their rent in the USA or they’re cleaning toilets, or overworked, with hardly any social life. Back home, they have their only chance to strut and brag. This notion that everybody's just living fabulously in the West is also reinforced by media images, by music videos and movies, so Vietnamese are bombarded by this nonstop seduction from the West, and America is best at this. She’s a go-go dancer who flashes everything but won’t even give you the cheapest feels, only deadly vaccines, bombs, degenerate music and hypocritical lectures, and she can go on and on.

This infatuation is common. Almost everyone believes it because most have never been to USA to see for themselves what the situation is like right now.

Leafbox:

I have a Cuban friend who's a refugee in Miami. He's been in the United States for 20 years, and he recently just went to San Francisco for the first time, and he couldn't believe it. He just could not believe the situation. This is a Cuban, he's like, "We don't even have food in Cuba." And he just couldn't understand the reality of San Francisco in California, and he just wanted to get back to Miami.

Linh Dinh:

Incredible squalor. People who live worse than animals all over the place.

Leafbox:

It's a very complicated issue. I think it has to do with the lack of religion and the lack of family and structure and just all kinds of issues and even possibly foreign influence. Going back to Vietnam, you write a lot about I have to be careful the words kind of the Corona madness and just the psyops all over the world. I'm curious, what are the psyops ongoing in Vietnam? What is the government selling, are they selling the American dream? Are they selling commerce? What are they selling to the people? What is the narrative-

Linh Dinh:

In regard with COVID or what?

Leafbox:

Well, not just COVID but I assume the Vietnamese is page in terms of the same madness as the rest of the world. In Vietnam, I’m just curious, what is the dream? Is the government controlling people by fear? Are they controlling people by a carrot of a mansion in the future? Because I've never been to Vietnam so I'm curious you as an American who's written about collapse in the West, how is the Vietnamese society keeping itself intact from the current levels of collapse that you see in the West?

Linh Dinh:

I mentioned the loosening of censorship in literature around 1989, but there was an overall shift, because hardcore communism just wasn't working. People were starving and there was no reason for Vietnamese to starve, so the government had to change its policies. Finally, it allowed people to do whatever they wanted, as long as they didn’t mess with the Communist Party. In Vietnam, the first thing you notice are all these small businesses everywhere. Every street is just filled with stores, and there are all these stores in alleys. Anyone can just open a store. I can open a store tomorrow without any license. I can just set up a table and sell food.

People here are left alone to just buy and sell and be themselves, and Vietnamese are very good at commerce, so life has improved. From 1990 onward, each year got better, but by 2000, there was still a lot of destitution. You’d see children begging or selling lottery tickets. In the last 20 years or so, most of this misery has disappeared, however. Many Vietnamese are their own bosses, with their little stores, or they’re walking around to sell stuff. I'm not saying everybody's doing well, but the mood is optimistic. Vietnam is selling electric cars in the USA. Did you know about that?

Leafbox:

No, but it seems like because of the growth people are just eager to grow. It's like Chile in the '90s, everyone was excited the future was coming.

Linh Dinh:

They have an electric car called VinFast, so Vietnamese are proud of that, though this car was not engineered or even designed by Vietnamese. A rich Vietnamese guy just hired people of various nationalities to slap together a car he can sell. Anyway, Vietnamese can see that they are making better stuff, the restaurants are looking better, the cafes are looking cooler and the nightclubs are glitzier, louder and more obnoxious. Everywhere they look, they see improvements, and their own lives have improved. It used to be very hard for Vietnamese to get a visa, but now, a bunch of countries, 54, to be exact, don’t even require a visa from Vietnamese.

Leafbox:

Developing.

Linh Dinh:

So they travel. You have all these YouTube vlogger who talk about the most obscure places, so Vietnamese are dressing better, eating better and traveling. At the convenience store near me, you can get maybe five different types of cheeses, plus sushi and Korean kimchi. Two blocks away is a French and Spanish restaurant. There are two excellent Italian restaurants here, and keep in mind Vung Tau is only Vietnam’s 15th largest city. Compared to Saigon, Hanoi, Nha Trang or Da Nang, etc., it’s very provincial. In Saigon, I can get a marrakesh burrito or some of the best pizzas anywhere.

The mood in Vietnam was very optimistic, then COVID came. Now, things are returning somewhat to normal, but it's still problematic because, for example, the Chinese tourists are not here. When the Chinese tourists were here, Vietnamese complained about them all the time, but Vietnamese love to complain about Chinese, period.

China this, Chinese that. When there were so many Chinese tourists here, everyone had a negative story about them, but now they’re gone, and dearly missed in many cities. It’s baffling to see China locking in its own citizens. Though some foreign tourists have returned to Vietnam, there's still a lot of uncertainty. The worst COVID trauma was last year’s lockdown that lasted over two months. It was a real horror because many people had hardly any living space. You might have four factory workers in a tiny room without air conditioning. To force them to live inside a steaming little cell like that, day after day, was torture.

Linh Dinh:

Now things are more or less normal. Over half of Vietnamese, though, still wear masks in public. This makes no sense because they take them off in cafes and restaurants, but put their masks back on when they get on a motorbike. I've taken a few photos of people wearing masks in the ocean. They’re taking a dip in the ocean, there's nobody around and they’re wearing a fucking mask! There is a psychosis here, which I find very annoying and disturbing, but most people are living fairly normally. When I first got back, I wasn't sure whether I had to wear a mask to go into a bank, for example, then I realized they didn't care, so I don't wear a mask anymore.

Leafbox:

Linh, going back to that psychosis, how did you evade the psychosis?

Linh Dinh:

How did I what?

Leafbox:

How did you evade the mind virus?

Linh Dinh:

This is funny, man, because when COVID broke out, I was in Laos. When somebody mentioned it, I thought it was just some minor whatever, so who cares? When I heard it was rather serious, I returned to Vietnam and went straight to the Chinese border.

There's a city, Lao Cai, that’s right across from China. There, you can see Chinese buildings and Chinese people across a narrow river. I had been there once, so I rushed to it, to be within fondling distance of Coronachan. In Lao Cai, I walked along the river and stared at the empty streets and rooms on the other side, at all the closed businesses. Every so often, there would be a solitary figure just walking, or standing inside a window. On the Vietnamese side, life was normal, but on the Chinese side, it was post apocalyptic. Keep in mind this was just some remote place on China’s very edge, 1,200 miles from Wuhan. I wasn’t sure if I was glimpsing the end of China. Maybe they would all die soon!

It was morbidly fascinating, this entire city with hardly anyone on the streets. I would see Chinese tourists returning to China with looks of distress. It’s like they were going back to sickness or death. Foolishly, I thought maybe I could sneak into China, but you know how it is, desires have their own rules. I had once crossed from Texas into Mexico illegally, and it was no big deal, so I thought I could do the same now. After over a month along the Chinese border, I could only see China but not smuggle myself into it, so when COVID erupted in South Korea, I flew there! I was chasing after COVID.

Leafbox:

Were you chasing COVID because you wanted to write about it, or you're just curious to see what the fuss was?

Linh Dinh:

Well, you have to see it to find out if there’s anything to write about it, but I’m the kind of guy who finds even a trip to 7/11 terribly exciting. Everything is worth writing about. At the beginning, I believed in the COVID narrative totally. I thought it was some horrific pandemic that's going to kill billions. So I ended up in South Korea for five months, because Vietnam had closed its borders, and so did Cambodia, and all of Asia, actually. Stuck in South Korea, I saw the contradictions of this COVID nonsense.

You probably know this already, but the Japanese and Koreans loved to wear masks anyway. Many Japanese wore masks long before COVID, and the South Koreans were nearly as bad. Japanese friends told me they wore masks to prevent themselves from spreading illnesses, not for self-protection. Still, it seemed overdone, if not farcical. Anyway, South Koreans would wear a mask on the subway, and they mostly wore masks walking down sidewalks. Inside a drinking or eating place, however, they took their masks off, of course, and there was no social distancing, so what's happening here? Since the Koreans loved to mingle, carouse and drink alcohol together in public, they had to ignore COVID rules.

Leafbox:

I understand that. No, I agree. I'm just trying to understand what in you Linh prevented you inoculated you from that mind virus? Is it the fact that you're American; from thinking that way.

Linh Dinh:

It's because I saw these contradictions.

Leafbox:

Most people don't see or question the contradictions they just accept it and they don't even question anything. So I'm trying to understand, where does your questioning nature come from? Is it the fact that you've been an alien in the US, the fact that you're a writer. I have many friends who accept everything, I've lost friends over the last two years. So I'm curious, where does it come from in you? That's what I'm asking.

Linh Dinh:

In Vietnam right now, my favorite part of the day is to walk outside at 6 in the morning. My first step outside, I'm always very happy. I love to be on the sidewalks. I love to be walking down the street. So I was not going to lock myself in out of fear. In Philadelphia, I always walked and always loved to be among people. Of course, when I write I have to be alone because writing is a solitary activity. But when I'm not writing, I walk around to look at people and talk to them. Even with COVID, I maintained this habit. Since South Korea was a very exciting place, with a lot of visual stimulation, I walked around constantly. I was eating out and drinking out, that was my compulsion, so I kept doing that, despite COVID.

So I was always among people and no one else showed any real fear either. When I first got to Seoul, most cafes were empty because people didn't know how to deal with this, but soon enough, people wandered out. Koreans also had this compulsion to eat, drink, mingle and laugh regularly. I visited more than a dozen South Korean cities, and each one was lively and near normal. Of course, there were weirdos who stayed inside, but paranoiacs and misanthropes exist in every society.

Anyway, I realized soon enough there's nothing to be afraid of. After five months in South Korea, I had to leave because if I was going to be stuck outside Vietnam, I might as well travel. I went to Serbia because there was no COVID test requirement or quarantine. Several Balkan countries were also similarly relaxed, so from Serbia, I could enter neighboring countries without hassles. I ended up in North Macedonia and Albania. Before returning to Vietnam, I was also in Lebanon, Egypt, Namibia and South Africa. All these places were more or less normal, and I never had to endure a lockdown. In Egypt, if you take the cheap train, you can't even move, man. You're touching four different bodies. Foreigners are not supposed to take third class train, but I did it anyway.

Leafbox:

I've been to India, it's the same. It's understandable. So I'm just curious, so while you're traveling around during the COVID and you're watching, obviously you're talking to friends who have been absorbed by the mind virus. What did you think of them, that the fear was overtaking the whole planet?

Linh Dinh:

Being in these places, I saw that life was normal, that people basically had no fear of this disease. In poorer places, people didn’t have much of a choice. They had to function normally to eat. In Sub-Saharan Africa, most people wisely shun these deadly jabs from the sinister West. During my five months in Windhoek, Namibia, the COVID “vaccination” center at a downtown shopping mall was nearly always empty. Most Namibians weren’t tricked into harming themselves.

When I started to read up on what’s going on, I came to realize there was an agenda behind this, then came the appearance of the genocidal jab. They’re trying to kill us. During the first year of COVID, only 35 people died in Vietnam, but after the Covid “vaccine” rollout, thousands started to die, and they’re still dying. Of course, the government and global media blamed it on COVID, and they’re also making all sorts of laughable excuses for healthy people dropping dead all over.

I'm pretty sure I caught COVID in Albania because I had never been so sick in my life. I was a total mess for about three weeks. Just lying in bed, I had to think maybe two hours before daring to shift positions, because it was just too painful. Everything was too painful. Still, I refused to go to the hospital. Though I didn't have friends or family nearby, my landlady was in the same apartment. Had I moaned loud enough, she would have taken me to the hospital, but that would have likely been fatal. Wrong treatment in hospitals worldwide murdered many COVID patients.

I was determined to just ride it out, so if I died, I died. Delirious, I had passing thoughts about jumping out my 8th floor window, but that would have left a very bad impression with the neighbors. Crazy Oriental came to Tirana to jump out window! Not a good exit.

Though I'd never been so sick, I took no medicines, saw no doctors and then it was over after roughly a month, with three weeks truly hellish. Though I was beyond exhausted, I couldn’t quite sleep, and I ate almost nothing day after day. It was too difficult to get up to do anything.

Leafbox:

So Linh, going back to this, I'm going to call it pre and post COVID. How has your writing and mindset changed now that we're in the post COVID era? Do you feel more free or less free or... I'm just curious, how do you feel? Are you more worried?

Linh Dinh:

Worry about what's going on?

Leafbox:

No, I'm just curious, do you feel more liberated or more carpe diem? What is you pre COVID, I get a sense of what you're like and now what are you post COVID? Has your writing changed or artistic mindset, you're still doing your walks at 6:00 AM. What's changed?

Linh Dinh:

My routines are the same. I'm still doing what I've always loved to do. The focus of my writing, though, has changed. The last book I published in USA was Postcards from the End of America, a collection of pieces about different places. This came out in January of 2017.

Around 2010, I was convinced the country was collapsing. With energy depletion, outsourcing of production and a degenerate culture, the US was clearly doomed, but as the world’s deadliest bully, Uncle Sam has been able to prolong his reckless, fuck you spree by running up record debts, which he won’t pay. Though essentially the poorest people on earth, Americans think they’re the richest, even as sidestep their neighbors’ bodies and shit on sidewalks.

Back then, I’d be invited to teach a writing class here and there. I never applied for a job. I routinely encouraged my students to go where they didn’t belong, and to write about the social, economic and political situation of the country. At UPenn, I told my students to take the subway and get off at an unknown stop, but not at night, of course, and if they were freaked out by anything, to haul their pretty ass back on the subway. At least one student couldn’t even get off her train, she was so intimidated, but at least no one was killed.

Way before COVID, I was convinced the country was unraveling, on every level. With COVID, I realized the people behind this have a bigger agenda. They're not just trying to destroy the USA, but the world as we know it. They want to get rid of “useless eaters” who, according to Yuval Noah Harari, don’t even have souls. He sure doesn’t, nor do Klaus Schwab and Albert Bourla. Always looking so earnest, Rochelle Walensky may have half a soul, made of papier-mâché.

First off, COVID “vaccines” are fraudulent, because they don’t prevent you from catching COVID. In fact, they increase your chance of catching just about everything. Here’s a headline from 9/12/22, “Ethically Unjustifiable”—Scientists from Harvard & Johns Hopkins Found Covid-19 Vaccines 98 Times Worse Than the Virus,” so there’s your science. I know people who have been injured by COVID “vaccines.” There's a bigger agenda, so I've been writing about that. As I learn more, I articulate what I know. You can’t just stand on the sideline and say, “It's not my business.” It's everyone’s business because this is the worst genocide ever. This is a tremendous battle that involves everybody.

As an intellectual, you must address this issue with as much honesty and understanding as you can muster, and I fault many people for not doing that. Many people who can write and apparently think very well are sidestepping obvious conclusions about what's going on. There's a huge failure among American intellectuals at the moment. This is a very shameful chapter in history, not just for the USA but many countries. Never before had so many “thinkers” been so cowardly and dishonest, but they have been trained to arrive at this for a long time.

Leafbox:

Do you find that critique missing from the left or from the right or…

Linh Dinh:

Both.

Leafbox:

Left and right don't even mean anything anymore.

Linh Dinh:

I never talk about left or right, by the way. I think that's too simplistic. Although I agree it is somewhat useful, I stay away from that division. Back to the failure in thinking and courage, people are afraid, and I'm talking about top intellectuals even. Since they don't want to lose their social standing, American intellectuals are very dishonest right now. They’re not articulating what they actually know, because they can't be so stupid to not recognize what's going on.

Leafbox:

Well that comes back to the question again, I think personally Linh, it has to do with the fact that you were shocked linguistically at a young age. Possibly when you have a multilingual mind it allows a flexibility in seeing things from different angles. I'm just trying to figure out why you think the other intellectuals aren't seeing the reality that you're seeing in front of you. They're just in a psychotic state, or what do you think? Why can't they break through? Maybe your conclusions are right, maybe they're wrong, but at least you're questioning things. You just think they're too scared because of social pressure.

Linh Dinh:

A typical American intellectual is likely to be associated with a university. That, right there, is a huge problem. To become a tenured professor, you must invest lots of time in the system. You’re likely to have a PhD, so that’s three degrees you’ve gotten. All your life, you’ve been trained to be super obedient so you can be hired permanently, so you can be safe within the system. Most American intellectuals, then, are exactly like circus animals. To become middle class, to be normal, that is, they had to jump through a thousand flaming hoops, so all their brain cells are singed, if not charcoaled. Now, they have mortgages to pay, and nearly all their associates are also academics, so there's enormous pressure to go along with each consensus. If it’s kosher to say men can give birth to babies, they must agree.

There's also a competitiveness at work, because there are only so many jobs, grants and prizes. You don't want to slip, you must hang on to what you have and you’re watching your friends, to see what they’re getting. To maintain or enhance your status, you don't just go along, but pander, so you become dishonest. In Vietnam, people in the Communist-sponsored Writers' Union are similar to American intellectuals in universities.

Leafbox:

It's another muzzle. I understand. It's just another blinder.

Linh Dinh:

There are punishments and rewards for thinking properly, so these careerists are always marching in lockstep, just like the Nazis they accuse everybody else of being. All the opinions are reinforced by their clones, so with COVID, you find this bizarre uniformity of opinions. Deep down, many must know something is seriously wrong, but they don't dare to articulate it.

Leafbox:

Going back to collapse have you read Dmitry Orlov, The Five Stages of Collapse? Is that where you first thought about that

Linh Dinh:

I read Orlov, and also James Howard Kunstler, about Peak Oil. Let's talk about Kunstler, who’s a fantastic writer. Though he's very good with energy depletion, he won’t address certain issues, so that's a serious problem. Recently, Kunstler actually suggested COVID was invented to bring down Donald Trump, “My personal theory is that the Covid-19 release was wholly and entirely about getting rid of Donald Trump and nothing else […]” Come on, man, you’ve got to be insane to think that. I find it sad Kunstler would say something so silly. Since he’s a very smart man, he must understand more than what he lets on..

Leafbox:

I'm just curious what you think about the multipolarity that's occurring right now in the world as the shift moves from the West towards Eurasia mean. For Vietnam that might be a positive I'm just curious how you see that politically or…

Linh Dinh:

The USA is still exerting a lot of influence. Look at what’s happening with Ukraine, with Europe adhering to American nonsense to the point of committing suicide. Uncle Sam makes Jim Jones look like Mother Teresa. European factories are shutting down, its businesses are going bankrupt and, soon enough, many of its people will freeze to death, all to contain Russia, which never threatened them

As for multipolarity, there are only two, with Uncle Sam on one side, and Russia and China on the other. It’s funny, but Western so-called intellectuals tend to go all out for an idol, so if they reject American hegemony, Putin or Xi Jinping must be the greatest, and I’m only talking about the fringe, of course. People in the mainstream can’t say anything nice about Putin. In the past, American thinkers have swooned over Lenin, Stalin, Mao or Castro, etc.

You can't be so naive as to think anyone necessarily has your best interest in mind. It's important to be open minded about every character and situation.

Vietnam has always been very nervous about China, because it's this huge neighbor right next door. Vietnam has to look out for its own interests while also accommodating China, because China's not going anywhere. That doesn't mean you’ll find many Vietnamese who believe China is a beacon for the future.

Leafbox:

I mean that almost seems like the healthier pragmatic view than choosing sides.

Linh Dinh:

Small countries are like that, but that's something Americans don't understand because they've never been in this situation. The fattest kid in the cafeteria, Uncle Sam’s used to pushing people around and stealing their lunches. He burps and farts about democracy and laughs at his own jokes. Small countries are always compromised because outside players are always messing with them.

Leafbox:

Linh, going back to a quick question about the university system and whatnot. I believe your wife is a business person, is that correct?

Linh Dinh:

No, she just sold stuff in a shopping mall.

Leafbox:

Oh, okay. I was just curious because I wonder if anchoring yourself outside the university system just gave you more freedom, and if you had advice to other writers or artists on how to maintain that freedom.

Linh Dinh:

I never finished college. I studied painting, so that was not a regular university to begin with. I'm just not a school person. Even in high school, I stopped going to classes at the end, but managed to graduate anyway. I just don't like to sit in a class. Though I never tried to become a professor, I ended up teaching anyway after I got published, but mostly, I just worked jobs I wasn’t any good at. I was a house painter, house cleaner and loose leaf filer, etc. The computer eliminated loose leaf filers, but that’s what I was in Washington DC in the 80’s.

Though working shit jobs to become a writer could have turned out very badly, it exposed me to all sorts of people, and this has helped me out. Since I had some college and had read a few books, I wasn’t really a blue collar guy, but I had to fit in with them. Quickly, I learned to admire their strength, and not just physically, but mentally and psychically. I couldn't believe how people could endure so much day in and day out, for decades. This perspective is the bedrock of my thinking.

Leafbox:

Do you know William Vollmann?

Linh Dinh:

Yeah.

Leafbox:

There's just a lot of parallels between your writing career and work experience. He's an outsider as well, he also writes a lot about poverty. Not just poverty, but he doesn't judge anyone, there's kind of a lack of judgment, which I find in your writing as well. So Linh, I know your time is valuable. I'm just curious, what is your advice to other young artists or just people in general. Or what can they take from your writing necessarily? What's the most important thing you want them taking…

Linh Dinh:

My advice would be to use your work experience to feed your writing. Let's say you are a waiter, Uber driver, go-go dancer or whatever. Though you may not love your job, use that to feed your writing. Use whatever you have to do to feed your writing, and be curious about everybody. Imagine yourself in their position. It's astounding what people must do just to get by, so pay attention to everybody and, again, pay close attention to how they talk. Many of them, if not most, might be more adept at language than you!

Don't gravitate towards people with power, glamor or fame. Since that’s the general inclination, check it, at least. Hang out with losers because you're already a loser, and if you're not, you'll be one soon enough.

I'm constantly reminded by how stupid I am. Walking down the street, I might mutter, “Shut the fuck up! You’re just a mentally ill piece of shit!” As long as there’s no bloodshed, it’s healthy to argue with yourself. Sometimes I forget there are people nearby, so they’re looking at me like, “What's wrong with this asshole?”

It’s OK, everybody is a loser. Failure, losing and collapse constitute our destiny. Like societies, each man will collapse.

That's how you die, but you don't just die instantly, but rather slowly. On the way up, you make a bunch of mistakes, and on the way down, you make more mistakes, but hopefully in between, you can say a few things that are memorable. You might even make someone feel a lot less lonely. If not, then fuck it, at least you tried!

Leafbox:

Great. Well, Linh, that's a perfect, positive, uplifting end.

Linh Dinh:

Was that positive?

Leafbox:

I think it is. I think people can take that message as a model for a sort of relaxed carpe diem. Linh, I think we could talk more and more but thank you so much for your time.